The Rise and Fall of the Jagat Sheths

The story of the Jagat Sheths, who once dominated the economy of Bengal and lay the foundations of Marwari enterprise in India, began with Hiranand Sahu, purportedly a jeweller-turned-moneylender, who is said to have left home in Nagaur in circa 1650, with the blessings of a Jain saint. His search for better prospects took him to Patna—a prosperous city and important business hub by then—where he started off with moneylending and banking operations. In addition, he started dealing in saltpeter, a commodity that was much in demand among European traders owing to its multifarious uses, not least of which was as an ingredient of gunpowder.

Hiranand Sahu prospered quickly, and as was wont among those involved in seventeenth century banking operations, he sent his sons to other cities to expand his scope of business. Son Manik Chand was sent to Dacca (now Dhaka), the then capital of (undivided) Bengal, with the twin motives of expanding the existing family banking network and simultaneously tapping the lucrative Dacca market which at the time was a trading Mecca for silk, cotton and opium. Manik Chand proved particularly gifted. He soon flourished and gradually took to financing large scale trade. In the process, he extended his financial clout to even befriending Murshid Kuli Khan, Emperor Aurangzeb’s appointed diwan of the Subah of Bengal. As diwan—and a rather able one at that—the treasury and all financial transactions gradually came under Manik Chand’s control. This brought him in serious conflict with Prince Azim-ush-Shan, the grandson of Emperor Aurangzeb, the then subedar (viceroy) of the Subah of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa, which necessitated his transfer to Mauksusabad (as Murshidabad was then known). Prince Azim-ush-Shan likewise was transferred to Patna. When Murshid Kuli Khan shifted base to Mauksusabad in 1704, his dear friend Manik Chand followed suit, shifting his headquarters to the new city and setting up a palatial residence in Mahimapur which stands to this day. In effect, Manik Chand became the collector of revenues and his treasurer and together they resolved to jointly develop the new city which Murshid Kuli Khan had renamed Murshidabad after himself. Manik Sheth is said to have spent enormous sums in the process.

Nagar Sheth, Manik Chand

Meanwhile, in Delhi, Emperor Aurangzeb’s breathed his last in 1707. His death marked the beginning of the decline of the mighty Mughal Empire with a quick succession of less able rulers hastening its disintegration. With the empire tottering, Murshid Kuli Khan saw his power and influence rising in Bengal. An old-timer from the reign of Aurangzeb, he was an able administrator and leader who brought about land and agrarian reforms, systematised revenue collection and promoted trade and commerce which brought prosperity and stability to the land. But he continued to pay a hefty yearly tribute to the emperor.

By 1717, the influence of the Mughals had waned sufficiently to let Murshid Kuli Khan exert his influence as the virtual ruler of Bengal. Trade with the Europeans flourished greatly under him, which further fuelled Manik Chand’s growth and financial clout as Murshid Kuli Khan’s banker, economic advisor and mentor. When Farrukh Siyar became emperor in 1712, cash strapped that he was like the latter day emperors, he had to turn to Murshid Kuli Khan. Finally, Manik Chand’s magnanimity provided the much-needed funds. Pleased with him, the emperor bestowed the title ‘Nagar Sheth’ upon him. It marked the beginning of

the Jagat Sheths’ reign as the financial

tsars of India.

Jagat Sheth, Fateh Chand

Manik Chand died in 1714. As he had no heir, his nephew and adopted son, Fateh Chand, took over the reins of the family fortunes. Fateh Chand proved even better than his predecessor and his expertise in financial matters and astuteness as a

banker–trader took the family to the peak of its luminescence, so much so that Emperor Mahmud Shah in 1723 bestowed the title ‘Jagat Sheth’ (Banker to the World) upon him. Fateh Chand’s banking and hundi network was extensive. It had a presence in all major cities and key trading hubs across the subcontinent. Moreover, the house enjoyed nearness to both the nawabs of Murshidabad and the Mughal emperors of Delhi. Given Bengal’s flourishing trade at the time, where the Dutch, the French and the English vied with each other for dominance, and the fact that in the aftermath of Murshid Kuli Khan’s death, the mints of Murshidabad and Dacca gradually came under Fateh Chand’s control, he virtually controlled the money market of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa and even beyond. Consequently, it became impossible for anyone to engage large scale inland or external trade without involving him.

At its height, the house of Fateh Chand Jagat Sheth acted as the nawab’s treasury, and considering the geographic extent of the Nawab of Murshidabad’s influence, operated much like a central bank. It loaned monies to zamindars, collected interest, dealt in bullion, had seigniorage rights and minted coins for both the state as well as foreign traders, financed trade, exchanged money, controlled exchange rates, operated extensive hundi operations, collected and retained two-thirds of the revenue from the Bengal-Bihar-Orissa province on behalf of the nawab, made remittances to the emperor, etc. The biggest trading houses of the time, including the English, Dutch and French East India Companies, sought to keep Fateh Chand in good humour and strove to gain his favours, even if it be in the form of a mere recommendation, because his word carried much weight. Because of the monopoly he enjoyed and the political influence he wielded, Fateh Chand was among the most illustrious, powerful and influential of the Jagat Sheths.

The richest man in the world

When Fateh Chand died in 1744, his grandson Madhab Rai (the son of his eldest son Anand Chand, who had predeceased him), took over as the next Jagat Sheth, while his cousin Swarup Chand (son of Fateh Chand’s second son) was bestowed the title ‘Maharaja’. The wheels of political fortune had meanwhile turned and Alivardi Khan was the nawab of Murshidabad now. Madhab Rai and Swarup Chand got on well with Alivardi Khan, with the latter continuing to support and respect the cousins, which in turn helped the duo expand their business horizon with newer avenues of income, though still within the broad purview of the banking, hundi, trading, minting and exchange operations that the Jagat Sheths were experts at. Around this time the Marathas are said to have repeatedly raided and looted Murshidabad, on one occasion even leaving the Jagat Sheths poorer by two crore rupees. But that supposedly did not dent their liquidity or fortunes in any significant way. To put the cousins’ wealth into perspective, popular folklore has it that they possessed so much gold and silver that it could stop the flow of the Bhagirathi.

And, according to East India Company historian Robert Orme, Madhab Rai Jagat Sheth was the richest man of the time in the known world.

The rise of the British

Alivardi Khan’s reign came to an end with his death in 1756. As he had no male heir, his grandson Siraj-ud-Dowlah succeeded him as Nawab of Bengal at the age of 23. Young, haughty and beset right from the outset with palace intrigues, threats of invasions, dissenting family members, scheming local rajas and other notables of the time, including Jagat Sheth, his year-long rule was troubled and marked by one of the darkest chapters of India’s history.

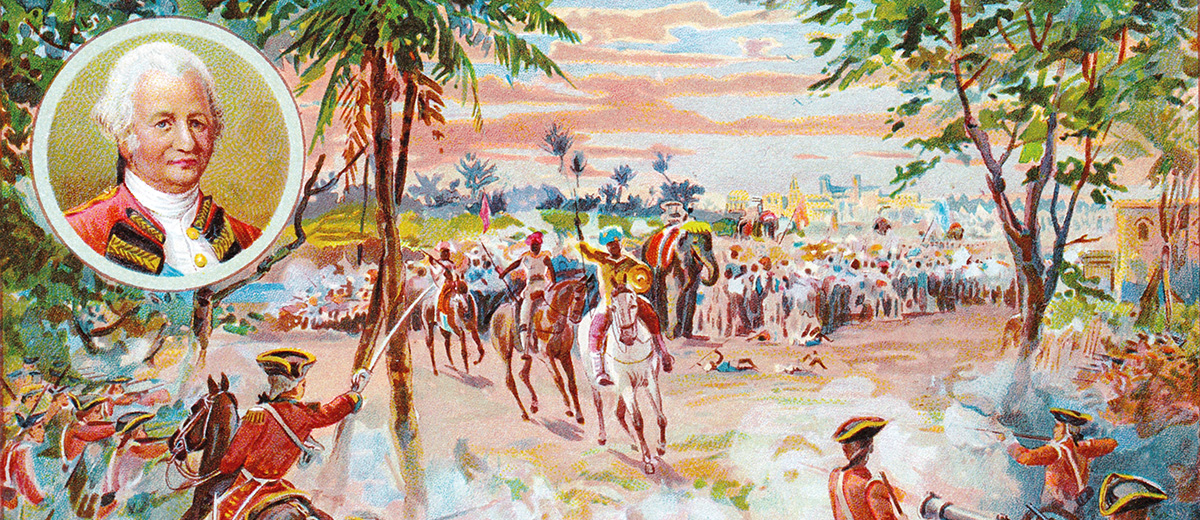

It all started with an ever-ambitious British East India Company seeking to further consolidate their position in Calcutta, much to the resentment of the Nawab Siraj-ud-Dowlah, who, history has it, put paid to their ambitions a crushing blow to the East India Company stronghold Fort William, in Calcutta, in 1756. It led to the capture of East India Company’s small private army and other British prisoners of war and their subsequent incarceration in a tiny, suffocating cell—the infamous ‘Black Hole of Calcutta’—which resulted in their death overnight. The incident, exaggerated by Company officials, fuelled outrage among the British, who swore punitive action against the nawab. This was made possible through the schemes of one of East India Company’s private military officers, Robert Clive, who with the connivance of Mir Jafar, the nawab’s chief of army; Omichund, a wealthy local merchant; Jagat Sheth and other subversive elements hatched a conspiracy to overthrow Siraj-ud-Dowlah. The imminent confrontation between the nawab’s army (or whatever part of it that was still loyal to him) and Robert Clive’s modest forces took place one fateful rainy day in June, 1757, on the banks of Bhagirathi. The nawab’s army was predictably defeated. A fleeing nawab was later captured and murdered by Mir Jafar’s son, Mir Miran’s men. The historically significant battle, better known as The Battle of Plassey, changed the course of Indian history in that it ultimately paved the path for British rule in India.

Gathering gloom

Mir Jafar, as agreed in his secret pact with Robert Clive, was appointed Nawab of Murshidabad, but being no more than a puppet ruler, he was forced to pay such exorbitant compensatory sums to the British (as per the terms of the pre-war treaty with Robert Clive) that it left the state bankrupt. Omichand never saw the cut (of the booty) he was promised, thanks to Robert Clive’s unscrupulous ways. And as for the Jagat Sheth cousins, things fared worse for them. Mir Kasim, who succeeded Mir Jafar as nawab, tried to restore Murshidabad to its former glory to the extent of even engaging the British—unsuccessfully. After his defeat, incensed at the treacherous role played by the Jagat Sheths during the Battle of Plassey, he murdered both Madhab Rai and Swaroop Chand and threw their bodies off the ramparts of the Monghyr Fort (in Bihar). This was in 1763. The Battle of Buxar followed in 1764 in which the British scored their second decisive victory against the combined forces of a beleaguered Mir Kasim, the Nawab of Bengal; Shuja-ud-Daulah, the Nawab Wazir of neighbouring Awadh province; and the fugitive Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II (who had taken refuge in Awadh).

The Battle of Buxar changed the status of the East India Company from a trading entity to a territorial power and turned them virtually into the masters of Bengal and Bihar. It helped them wrest diwani rights from Emperor Shah Alam II at the Treaty of Allahabad which allowed them to directly collect revenues in Bengal and Bihar. It marked the beginning of Britsh rule in India and the turning point of the reversal of Jagat Sheths’ fortunes.

Bitter twist of fate

With the ascent of the British, the Jagat Sheths’ once stranglehold over the money market of Bengal as state bankers and treasurers diminished. The revenues that the British collected and the trading grants they enjoyed after the Treaty of Allahabad obviated their dependence on the Jagat Sheths for loans or selling of bullion to them (to be minted into currency). Further, the British had long desired for a mint in Calcutta which would reduce their dependence on Jagat Sheths’ Murshidabad mint and this became possible when Warren Hastings, the first Governor-General of Bengal, transferred the state treasury from Murshidabad to Calcutta.

After Madhab Rai and Swaroop Chand’s death, Kushal Chand (son of Madhab Rai) was granted the title Jagat Sheth, while Udwat Chand (son of Swaroop Chand) was bestowed the title ‘Maharaja’. Kushal Chand was said to have been extravagant, spending exorbitantly and donating huge amounts, in spite of the fact that their businesses were falling apart. There also are rumours about Kushal Chand having stashed away a huge cache of precious metals, jewels, coins and

other valuables; but to this day, it has remains untraced.

With their traditional sources of income drying up gradually, in a bitter twist of fate, the Jagat Sheths now had to turn to the British to meet their expenses. Robert Clive offered them a yearly grant of three lakh rupees, but Kushal Chand, too proud to accept such paltry a sum (when the monthly household expenses of the family, even in these times of adversity, was no less than one lakh rupees) declined it.

The last of the Jagat Sheths

Kushal Chand died at 39 without an heir, as his son Gokul Chand had died when he was barely 20. He was succeeded by Harreck Chand, who is credited with having built the still surviving Kathgola Palace in Murshidabad. Harreck Chand had two sons: Indra Chand and Bishen Chand. The family treasures had almost dried up by now and the last of the Jagat Sheths’ fabulous treasures were just memories of the past. Indra Chand, who succeeded Harreck Chand, was later succeeded by his son Gobind Chand, under whom the last of the family treasures were sold off to make ends meet. The family had no choice but to turn to the British again, who mercifully granted a pension in view of the services rendered by his ancestors to the British. Gobind Chand had no issue and so adopted Gopal Chand. The family pension was now reduced to r1,200. After Gopal Chand’s death, his widow adopted Golab Chand, whose son Fateh Chand was the last notable of the long lineage of wealthy, illustrious bankers, who once were the financial emperors of India. After Fateh Chand’s death in 1912, almost nothing was left of the once mighty Jagat Sheths except perhaps the rebuilt house at Mahimapur, the Kathgola Palace and the Adinath Temple within it. As if nature too had turned against them, the grander edifices of the Jagat Sheths were either swallowed up by the meandering Bhagirathi or devastated by the Great Assam Earthquake of 1897.