The Rags-to-Riches Story of Ramkrishna Dalmia

It was a twist of fate that launched Ramkrishna Dalmia on the road to success, glory and fame, and it was again the hand of destiny that left him with fragments of the massive industrial empire he had built from nothing. In between all this lies the saga of a financial and entrepreneurial genius whose drive, courage and extraordinary business acumen merits the tribute we pay him.

FOR A SEMI-LITERATE MAN WHO ROSE FROM POVERTY TO BE ONE OF THE NATION’S

FOR A SEMI-LITERATE MAN WHO ROSE FROM POVERTY TO BE ONE OF THE NATION’S

greatest industrialists, the story of the rise of Ramkrishna Dalmia inspires awe, respect and commendation. Here is a man who started his career from scratch and went on to set up scores of mills and factories, despite the prohibitive climate of the times when no attempt was spared by the ruling British to stifle the native industry. These successes not only brought him wealth, fame and glory beyond expectation, but also contributed to national growth in a way that has seen few parallels since. Sadly, for the man whose name remains emblazoned in India’s industrial horizon as one of its greatest achievers, Ramkrishna Dalmia’s contributions remain obscured under the veils of controversy that dogged both his entrepreneurial and personal lives. But despite this, after all the dust settles, what emerges is a financial and entrepreneurial genius whose legacy continues to influence India’s corporate machinery to this day.

Early life

Early life

Ramkrishna Dalmia was born in Chirawa, a small village in Rajasthan, on April 7, 1893. Driven by poverty, he left home at an early age with his family to resettle in Calcutta (now Kolkata), the then business capital of India. When just 18, his father passed away, leaving little behind, whereupon the onus of supporting the entire family (this included his wife, mother, grandmother and younger brother) fell upon him. To help the family pull through, Ramkrishna’s maternal uncle, Motilal Jhunjhunwala, offered him employment in his bullion business. With a modicum of basic arithmetic, English and Mahajani (an accounting script used by Marwari firms of the time) that he had picked up from a village teacher back home, he would decipher coded telegrams that the firm would receive from bullion agents in London.

Exposure to these enciphered messages gave him insight of the bullion business and its intricacies, prompting him to try his hand at speculating (in silver) to supplement his income. Unfortunately, his very first dealings came a cropper, earning him discredit and disrepute. The loss he incurred left

his uncle so sore that he severed relations with him.

A windfall

Having lost his means of livelihood, Dalmia turned to brokerage, armed with little except an inherent Marwari acumen for business and a handful of contacts. Despondent and eager to know what fate had in store for him, he made his way one day to Pandit Motilal Biala (of Fatehpur, Rajasthan), a man of saintly disposition, who also was a great astrologer. After studying his horoscope, the pandit predicted that within a month-and-a-half he would make one lakh rupees. True enough, lady luck smiled as predicted and through a queer twist of fate, he had made a profit of R1,56,000 from a bullion deal that was meant to be cancelled. It was as if there was a divine hand in play, bestowing this largesse upon him.

The lucky break led him to speculate in other commodities as well. To make good for his initial shortcomings (as a speculator), he made it a point to settle his credit, past or present, and ensured honest dealings with his associates which helped him put both his reputation and his businesses on firmer ground. During these years, he struck a partnership with one Baldeo Dasji Nathani of the Calcutta Share & Stock Exchange, a pious and trustworthy man, whose ideals were to shape his outlook towards both business and life in general.

The making of a business empire

The making of a business empire

Success in the speculation business brought about diversification, taking him one fateful day to Dinapore (in Bihar), where he established a trading business. During one of his visits there, the visionary in him saw great prospect in setting up a sugar mill in the area. To put his idea into motion, he joined hands with a well-known local zamindar, Nirmal Kumar Jain (of Arrah), with which the much contemplated sugar mill saw the light of day in 1932. Established in Bihta, near Dinapore, it was called The South Behar Sugar Mills Ltd and was the biggest sugar mill of the time in India, boasting adjoining company-owned sugar cane fields that ensured a steady supply of cane.

Meanwhile, Ramkrishna Dalmia was on the lookout for a suitable match for his daughter, Rama, settling finally for Sahu Shanti Prasad Jain—this was in 1932—who hailed from an illustrious family of landlords and financiers from Najibabad (UP). A remarkable and widely read man, Shanti Prasad was gifted in matters related to finance, economics and commerce, which made him a perfect fit for Dalmia’s fast-expanding businesses as a partner of the firm. He was to later control the group’s concerns in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa (now Odisha) as partner, while Shriyans Prasad Jain, (Shanti Prasad Jain’s brother-in-law), who by and by had also come to be associated with the group, looked after the company’s interests in the then Central Provinces, the Bombay Presidency and Southern India.

Along the journey, Ramkrishna Dalmia also took his younger brother Jaidayal along to assist him in his expanding business. A keen and dedicated learner, Jaidayal not only proved to be an able partner in growth, but given his interest in machinery, he was to later ably manage all technical aspects of the group’s factories in Dalmianagar (an enormous industrial township that later housed many of Dalmia’s companies) including scouring the world for latest technologies and procuring state-of-the-art machinery for their firm, Dalmia Industries.

With the trio’s combined abilities, a second sugar mill came soon after at Dehri-on-Sone, in Rohtas district in Bihar (the site of the future Dalmianagar). More sugar mills followed such as S K G Sugar Ltd, in Saran, Bihar; The Raza Sugar Co Ltd (in 1932), in Rampur; The Buland Sugar Co Ltd, also in Rampur; and a second sugar mill by the name of S K G Sugar Ltd, in Champaran, Bihar.

The next phase of growth for the firm (now known as Dalmia-Jain & Co Ltd) came in the mid-thirties, by way of a network of cement plants in key locations around the country, which were to be Ramkrishna Dalmia’s most significant contribution to national growth. The objective being to take on the monopoly of ACC Ltd, the reigning name at the time, the brothers imported improved machinery and superior technology, triggering off a price war with the British, which had to be finally settled through compromise. The biggest of the group’s cement factories was at Dalmianagar (as a part of Rohtas Industries Ltd). There was another large plant in Shantinagar (a township near Karachi, now in Pakistan, named after Shanti Prasad Jain), under the Dalmia Cement Limited banner. Dalmia Cement owned a couple of smaller plants as well, one at Dandot (now in Pakistan) and the other at Dalmiapuram, in the then Presidency of Madras. Further, the group owned a plant at Dalmia Dadri (now in Haryana).

The successful setting up of these factories triggered a second expansion spree. Starting with the acquisition of Bharat Insurance Company Ltd in 1936, Dalmia went on to establish National Safe Deposit and Cold Storage Ltd in 1937 (a chain of strong rooms with massive iron vaults and storage facilities in Calcutta, Lucknow and Kanpur) and later Bharat Fire and General Insurance Ltd in 1943, a pioneering general insurance company. The same year he established Bharat Bank Ltd, which was to grow prodigiously to boast as many as 292 branch offices by Independence, catering to the needs of local markets and industries.

By now, the Dalmia-Jain Group (now known as Dalmia-Jain Enterprises) ranked second to only the Birlas and the Tatas. Continuing to expand, the group next acquired majority stake in three Andrew Yule jute mills (The Albion Jute Mills Ltd, Lothian Jute Mills Co Ltd and New Central Jute Mills Ltd) and later purchased two flourishing Bombay-based (now Mumbai) mills in 1946: the Madhowji Dharamsi Manufacturing Co Ltd and the Sir Sapurji Broacha Mill Ltd. Soon after, the group acquired controlling interests in media giant Bennett, Coleman & Co Ltd, and then Bharat Journal Ltd, which like the former also published a number of English and Hindi dailies.

In the years following World War II, the Dalmia-Jain group forayed into the automotive sector with the purchase of over 50,000 American vehicles, including jeeps, weapon carriers and command cars. It repaired and reconditioned these vehicles at the workshops of Allen Berry & Co Ltd, a new company created for the purpose, which functioned in tandem with the group’s aviation company, Dalmia-Jain Airways Ltd (the company had been originally incepted as Indian National Airways Ltd by Ramkrishna Dalmia in 1933, its objective being to link up with other airways and connect up-country destinations with existing trunk routes). Further, the group extended its presence in railways too, mainly to facilitate carriage of raw materials to Dalmianagar . Next, it took control of several collieries, namely, the Kharkhari Coal Co at Junardeo, in the Central Province; Maheshpur Collieries Ltd, in Jharia; and Bharat Collieries Ltd, which worked mines in Jharia, Baraboni and Raniganj.

In addition to these, Dalmia-Jain Enterprises owned a string of others companies such as Patiala Biscuit Manufacturers Ltd, in the then Patiala State, which produced biscuits and a range of other food products; Lesco Chemical Works Ltd, which manufactured pharmaceutical products in Kanpur; Dhrangadhra Chemical Works, which produced soda ash, sodium bicarbonate, etc, in Kathiawar, Gujarat; Rampur Distillery & Chemical Works Ltd, which utilised the molasses produced at the group’s sugar mills to manufacture spirits and liquors; Rampur Maize Products Ltd, which produced glucose, starch and similar food products; and Shevaroy Bauxite Products Ltd, located in Yercaud (South India), which dealt in bauxite, emery and grinding paste. Some of these companies were controlled and managed by Govan Brothers Ltd, a British firm acquired by the Dalmia-Jain Enterprises.

Though many of the group’s interests lay scattered around the country, the jewel in the crown was Dalmianagar, a humming 3,800-acre industrial township that housed the mammoth Rohtas Industries Ltd, an umbrella organisation that had a number of companies and factories under it. These included a sugar factory, a chemical plant, an acid plant, a plywood factory, a vanaspati plant, a cement plant, an asbestos cement factory, a paper and hard pressed board factory, a central 12,000 KW power house that supplied power to both the group’s factories and the Bihar Government and a central workshop for spare parts. The township also had all-round facilities for the staff members and workers of these factories and their families.

A parting of ways

Sadly, for a business conglomerate that had grown to such gargantuan proportions in so short a time, its disintegration was just about as quick. Just when the group seemed poised for a long, prosperous haul with India’s Independence knocking on the doors, its partners chose to bring the curtains down on its trailblazing run by choosing to go their separate ways. Though this was done unofficially and amicably, it nevertheless, resulted in the group being divided between the Jains and the Dalmias first and then between the brothers Ramkrishna and Jaidayal. After this partition, Ramkrishna Dalmia went on to acquire controlling interests in Punjab National Bank, establish another cement factory at Sawai Madhopur, in Rajasthan, and acquire the Keventer’s dairy business in Delhi.

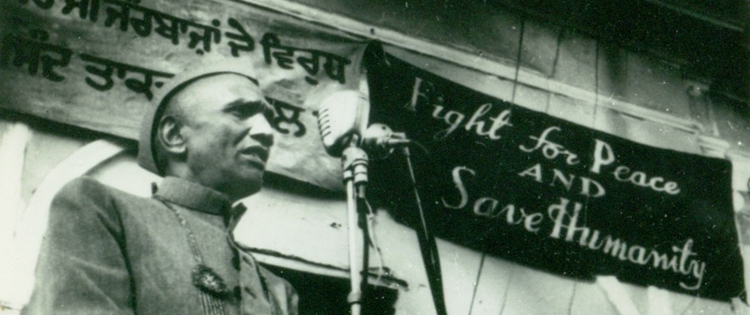

Brush with politics

Dalmia’s rise as an industrialist brought him in contact with many eminent personalities of the time such as Mahatma Gandhi, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Jamnalal Bajaj, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Dr Rajendra Prasad and Jayaprakash Narayan. Though he shared cordial relations with most of them, by far it was M A Jinnah that he was close to, whom he regarded a dear friend and whose bungalow at 10, Aurangzeb Road he later bought at the time of Partition. Given his concern for issues that influenced the industry and the country and his dedication to the cow protection cause, coupled with the fact that he was an ardent nationalist, Ramkrishna Dalmia often expressed dissatisfaction with some of the policies of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, the leader of the ruling Indian National Congress party and independent India’s first prime minister. Also, he openly criticised him for the Partition and the plight of refugees. Be it political backlash, or a classic case of a man who was the proverbial architect of his fate, or the long arm of law catching up with an act of indiscretion, in 1956, based on the findings of the Vivian Bose Enquiry Commission (appointed by the Nehru government), Ramkrishna Dalmia was accused of misappropriation of funds and stock market manipulations and incarcerated. Consequently, some of his companies which had got embroiled in controversy suffered. Worse still, he lost his star performers, Bennett Coleman and Co Ltd and the cement factory at Sawai Madhopur—he had to sell them off to Shanti Prasad Jain—which dealt a severe blow to his future as an industrialist. The companies under his partners (Shanti Prasad Jain and Jaidayal Dalmia), however, continued to flourish, as some of them do till today, especially Bennett Coleman & Co Ltd.

Personal life

Personal life

As a man, Ramkrishna Dalmia was sparsely built, almost to the point of emaciation, but he was strong both mentally and physically and had an extraordinary memory. Despite being the architect of a mammoth industrial empire, which no doubt called for inner drive, untold financial resources and a hardwired business sense, he lived a simple life, ate simple food and preferred austerity to a life of luxury. He was also intensely spiritual and philosophic and a litterateur at heart. A self-taught and widely-read man, about whom stories abound of picking up Bengali after reading street signage and learning English under the streetlights of Calcutta, he went on to author several books such as A Guide to Bliss, Fearlessness and Divine Law.

He was well versed with Hindu scriptures, the Bible and the Koran and had studied Vedantic literature, including Panch Dashi and Yoga Vashistha and the works of Swami Vivekananda and Swami Ramatirtha. It was perhaps this hunger for literature (and possibly cultural refinement) that led him to marry well-educated and sometimes scholarly women. Among them was Saraswati, the fourth of his six wives, with whom he lived most of his life and to whom he willed the lion’s share of his assets, or whatever was left of it at the time of his death. His other wives, in chronological order, were Narbada Devi, Durga Devi, Pritam, Asha and Dinesh Nandini, of whom Narbadadevi had and Durgadevi were village women. Narbadadevi had died when he was just 16.

Speaking about his multiple marriages, a contrite Dalmia was to later write in his autobiography, “I have married many a time and I feel that according to present day ideals, I have not set a good example… I have brought trouble upon myself with my eyes open… But these troubles have had a salutary effect… I consider these troubles as dumb-bells for spiritual exercise to purify my soul.”

Ramkrishna Dalmia’s life actually was an enigmatic mix of saintly qualities and wrongdoing, which prompted him to once say, “… Such is my life—peculiar in both right and wrongdoing.” The incarceration and the consequent losses he suffered would have rankled most others, but not Ramkrishna Dalmia—his was a forgiving nature that, according to him, had been inculcated by his exceedingly philanthropic great-grandfather, Shri Kashiramji, and his very first business partner, the saintly Baldeo Dasji Nathani.

A philanthropist

Having come up the hard way, Ramkrishna Dalmia understood the plight of the have-nots and the underprivileged, which prompted him to be generous with those in distress. There are reported instances of him having even mortgaged personal property and family jewellery to raise money for those in need. His largesse saw to the establishment of several schools for boys and girls and institution of scholarships and grants for the cause of higher education. His monetary contributions to the cause of nationalism are also well known, especially to Gandhiji’s Salt Satyagraha movement, which he financed heavily. His donation towards the establishment of the Delhi Public Library also merits special mention, as is borne out by a marble plaque at the entrance of the library. A second plaque expounding the ‘One-World Government’ concept mooted by him in 1948 also finds place in the library.

End of an era

End of an era

Ramkrishna Dalmia died on September 26, 1978, after a prolonged illness, at the age of 85. His demise triggered an outpouring of tribute from politicians and industrialists alike such as Jayaprakash Narayan, Jagjivan Ram (the then Union Minister of Defense), K N Modi and Sitaram Jaipuria. But perhaps the most defining of them all was the one from former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, the daughter of his once bitter opponent, Jawaharlal Nehru, who said: “His services in the industrial and social spheres of the country will always be remembered… he was very large hearted and philanthropic and his demise will be equally mourned by his family members and countrymen.”