The Marwari Heritage

Marwari Entrepreneurship in Pre-Independent India

Marwari Entrepreneurship in Pre-Independent India

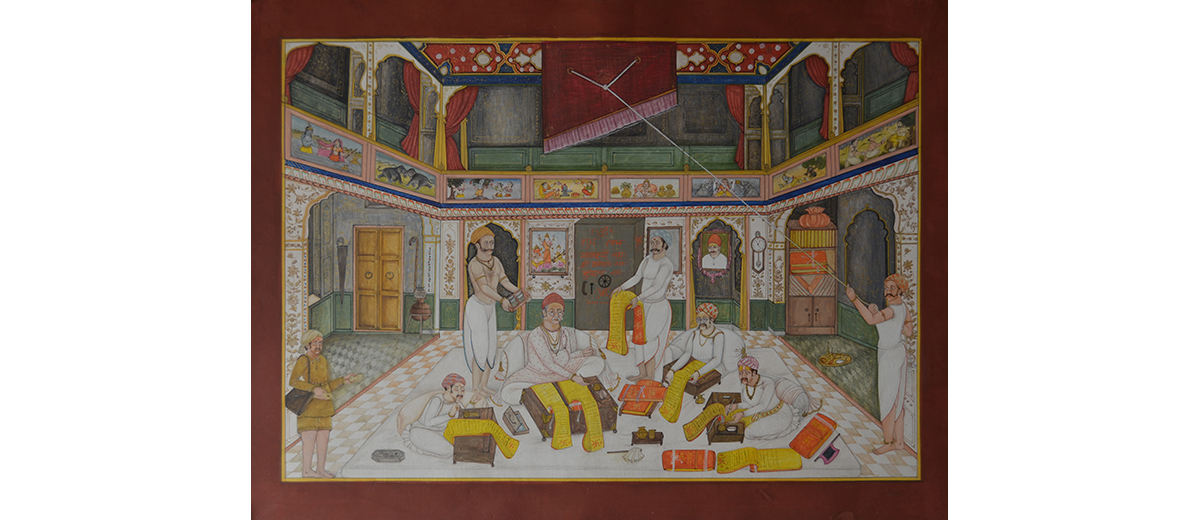

By the eighteenth century, the business atmosphere in Rajputana made the rulers of each of its states aware that the cooperation of the Marwaris was necessary to augment their revenue. During the Mughal rule the popular saying went: ‘Pahale shah, phir badshah — first a businessman, then an emperor.’ A stage came when the Marwaris began to be divided, just like property, on the distribution of inherited assets amongst the rajas and feudal lords. When Maharaja Karni Singh of Bikaner was getting married, a Vaishya, Alam Chand, was asked to escort his bride. This example is illustrative of the fact that the Marwaris were considered an integral part of the state and shouldered the responsibility of the state treasury.

The social significance of the Marwaris can be further gauged from the fact that the rajas and feudal lords of Rajputana were keen to get the largest possible number of Marwaris to settle in their respective territories. The status of a town was judged by the number of seths living in it, because the taxes and levies collected by the latter strengthened the state’s financial position. The rajas even realised that the cities could become prosperous through to trading which only the Marwaris seemed able to do. The seths were, therefore, regarded as the pillars or building blocks of a city’s economy. Extending great honour and privileges to them, the rajas offered them territories over which they would have direct jurisdiction rather than those belonging to thikanedars, where the seths would have been subservient to the thikanedars.

The common belief that ‘Banij karega bania—the bania would always go in for business,’ was augmented by the jagirdars’ opinion that ‘Bania meve ka rookh huve—the bania was like a tree of dry fruits.’ Many renowned seths were invited to settle in Jaipur State and allotted houses and shops free of cost. They were exempted from levies on business deals like their counterparts in Bikaner, Punjab and Delhi. Consequently, many moved to Jaipur.

Masters of Business Acumen

Masters of Business Acumen

Besides a strong body of networking, the Marwaris had access to credit and capital—in other words, the power of finance. Traders accumulated capital through commercial transactions and credit was the sine qua non of the trading fraternity. Port merchants supplied their imports on three-six month credit periods to their representatives based in other states of India. Similarly, merchants acquired cotton and jute from the farmers by granting them credit for the crop season. Thus, the key to the process lay in the Marwari business acumen in manipulation of credit. Over a period, due to thriving trade practices in lands beyond their home state of Rajputana, Marwari businessmen managed to generate surplus capital resources, which later enabled them to play a dominant role in the growth and economic development of the nation, even in pre-independent India.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, many Marwaris began opening shops outside Rajputana. The ancestors of the famous Dhadda family of Bikaner opened a firm called Tiloksi Amarsi in Benaras about 200 years ago. The descendants of Tiloksi established the firm Amarsi Sujanmal in Hyderabad. His son, in turn, extended the business up to Lahore and Amritsar in Punjab. Dughodia Harjimal of Rajaldesar began his cloth business about 200 years ago in Ajimganj. In 1815, Dwarka Kothari was running a shop in Mirzapur. At approximately the same time, another merchant, Chaturbhuj Poddar, had reached Punjab for business. His descendants were popularly known as ‘Saat peedhiyan shah – shahs of seven generations.’ In 1833, Mirzamal’s firm in Bombay was exporting shawls, spices, ivory and other goods to England. Churu’s firm Anantram Shivprasad dealt in sarafa, insurance and opium in Mirzapur, Farrukhabad and other cities, and built kothis for his family. Indeed, the existence of trade routes helped the Marwaris to expand their network further. Military and commercial needs ensured that various towns of Rajputana were linked with the chief trade routes of the country. Shekhawati had already been regarded as a major trade centre even before the tenth century. Many towns were then centres of trade: prominent among them were Bhilwara in Mewar, Malpura and Sanganer in Jaipur, Pali in Jodhpur and Churu and Sujangarh in Bikaner. Pali was the major centre of international trade.

Mohanram Saraogi of Churu established his banking business in Khurja and other places all over India. This found mention in the Imperial Gazetteer of India. At almost the same time, Ghansi of Bikaner reached Indore to distribute rations to Sawansukh Holkar’s army. In 1823, Seth Rukmanand of Churu set up a banking business in Calcutta through his firm named Rukamchand Vridhichand. Seth Jesraj Chunnilal and Navrangram of Bidasar reached Tejpur and Guwahati in Assam. In 1839, Sadasukh of Bikaner opened Sadasukhdas Gambhirdas in Calcutta. This firm dealt in gold, silver and corals. In 1845, Chetram became an agent in Calcutta and opened Chetram Ramvilas. In 1846, Raghunath Pachhisiya of Nohar started a cloth business in Calcutta and opened a firm named Raghunathdas Shivlal. In 1847, Ramkishandas Khemka of Ratangiri established Nathuram Ramkishandas. In this manner, the business of the Marwaris spread all over India. Sojiram Hardayal’s firm was the leader in the opium trade of Calcutta. It had also opened a branch office in China. Most of the firms in Central India were owned by Marwaris, and the famous firm of Chimanaram Singhania paid Rs 27.50 lakhs to the government as tax on the opium business alone.

An interesting procedure was followed to convey the current rates of opium in Calcutta to the merchants of Churu. The existing rates were wired to Jaipur. On receiving them, agents in Jaipur would rush to a hillock on the outskirts of the city and, employing mirrors as reflectors, they would flash the rates by using pre-arranged signals that were received by another agent atop Harsh Hill just outside the town limits of Sikar. From there, the quote was further transmitted to another hill in Jhunjhunu, and from that point, it was relayed to Churu atop Ghunghu Ghore. When the signal was received at Churu, a young, athletic man would run into the city and announce the rates to the merchants. Large, unwieldy mirrors were used for this important operation, and if urgent information had to be passed during the night, small, controlled explosions or fires using gunpowder were utilised along the same route.

Spread in Prosperity

From 1860 onwards, massive Marwari migrations took place towards east India. By 1911, there were 15,000 Marwaris in Calcutta and 75,000 in Bihar, Orissa, Bengal and Assam. They established their dominance in the field of indigenous banking soon thereafter. The banias became indispensible to British cotton clothimporting firms from 1870 to 1900. The Marwari merchants controlled the opium market even before 1860. Marwari merchants entered the jute trade in 1870, and by 1914 trade was controlled predominantly by them. During the First World War, the control of key speculative markets, import of cotton cloth and the jute trade resulted in war profits, which enabled some Marwaris to enter the industrial sector.

In central and western India, apart from the incidental investments of a few major banking firms, most of the available profit from trade and moneylending was invested in land. The Bombay community’s Shekhawati component gained a respectable position in speculative markets, especially stocks and cotton, along with trade in opium, cloth and cotton. However, vigorous competition, especially from various Gujarati commercial groups, did not allow them to achieve as dominant a position as in Calcutta. Before the First World War, a few Marwari merchants had been instrumental in setting up mills for others in Bombay. After the War, however, several started mills of their own. Similarly, in Hyderabad and Indore, war profits enabled the merchants to freely construct cotton textile and carpet mills.

Within a short span of time between 1857 and the end of the First World War in 1918, a small group of Marwaris in Calcutta, numbering fewer than 15,000, started trading from the port. They gradually made further inroads and eventually launched some of the first major Indian-owned firms that manufactured indigenous goods in eastern India and traded in those goods.

Wealth Begets Wealth

Most Marwari firms were engaged primarily in the banking, hundi and bullion business. Some large firms had earned a name in banking: while their head offices were in Shekhawati, Ajmer and Bikaner, their branches were situated all over the country. Each princely state in Rajputana had its own currency, which was converted into other currencies by traders known as sarafs who earned large profits out of this business. In 1835, Boyilo, a scholar, recorded that the bankers of Jodhpur and Phalaudi lent money to traders at a monthly interest of half per cent. In Calcutta, the dominance of Marwari banks was illustrated when the 1860 business directory listed at least fifty per cent of its members as Marwaris, with those from Ramgarh being predominant. The National Trade Board of Bengal complained about the Marwari leaders of Calcutta’s Indian banking system, alleging that they loaned money to businessmen of their own community instead of investing it for the general good, thus preventing other traders from functioning effectively. V.I. Pavlov, a writer, endorsed the business monopoly of the Marwaris in Bengal. D.R. Gadgil, an eminent scholar, attributed their success to their ability and competence in banking. After 1860, the Marwaris became the undisputed leaders in banking and trade.

Apart from the Nawab of Hyderabad giving sole charge of the state treasury to the Marwaris, after 1873, most of the bankers of Hyderabad were Marwaris. Raja Govinddas Pitti and Ganeriwal, two prominent Marwaris, even fixed the rates of taxation. Srichand was a renowned banker of Hyderabad, whose firm Seth Srichand Raghunathdas had many branches. By the latter half of the nineteenth century, many Marwaris became bankers of the British. Mirzamal Poddar extended loans to Maharaja Ranjit Singh many times. Riyanwale Seth and Bansilal Abirchand worked as treasurers for the British in many districts of Punjab. Rai Bahadur Ramchandra Mantri was the banker of the British Trade Agency at Yangtung and Gyansi, while pursuing his own trading business in China. C.H. Cosvet identified Seth Gokuldas of Jabalpur as the wealthiest banker of the Central Provinces. Marwari bankers established themselves in virtually every city of north India. Among the prominent bankers of Indore was Saroopchand Hukamchand. In Maharashtra, Bansilal Abirchand was acknowledged as the most prominent banker. Nagpur Bank was founded by him.

The Old Guard: Karamyogis to the Core

The gregarious Marwari community is almost synonymous with business in India. Starting out as traders and becoming a flourishing industrial community, the Marwaris played a pivotal role in changing the face of Independent India. Enriched by a centuries-old, rich, cultural heritage, people have always been the heart and soul of the community. This people-centric approach has extended to the present-day generation of Marwaris as well. Karamyogis to the core, salutations to the contribution of this traditional yet progressive community, and the humane values imbued by its founding fathers, can never be sufficient. Some prominent stalwarts feature in the photographs in this book but there are many more. Names which come to mind are R.N. Bagla, P.D. Agarwal, Indrachand Bagani, Ganeshdas Bagaria, B.P. Bajoria, Bhuramal Chaudhary, Binjraj Chaudhary, Lachhiram Churiwal, Jaidayal Dalmia, Kishorilal Dhandhania, Motichand Dhandhia, Nandlal Madhavlal Dhoot, Ramkishan Dhoot, Sanehiram Dungarmal, Shivbux Goenka, Tolaram Goenka, Phoolchand Halwasia, Purshottamdas Halwasia, Ashok Jain, Sahu Shanti Prasad Jain, Gangabux Kanoria, Laksminarain Kanoria, Radhakrishan Kanoria, Matadeen Khaitan, Surajmal Khemka, Pannalal Lahoti, Radhakrishan Lahoti, Lala Shriram, Shyamsunderlal Loiwal, Vishambarlal Maheshwari, Piramal Makharia, Radheshyam R. Morarka, Badridas Mukim, Vinod Neotia, Rameshwarlal Nopani, Vidya Sagar Oswal, Gopikrishna Piramal, Babulal Poddar, Bimal Kumar Poddar, Rampratap, Krishan Bihari Rathi, Jugalkishore Ruia, Nand Kishore Ruia, Sarup Chand Prithviraj Rungta, Motilal Sanghi, Anandram Saraf, Nathuram Saraf, Onkarmal Saraf, Kamal Nayan Saraogi, Pannalal Saraogi, Seth Govardhandas, Seth Lachchiram, Juggilal Singhania, Padampat Singhania, Nandlal Tantia, and Shivprasad Tulsyan.

These stalwarts became legends in the modern industrial world. There is hardly any sphere of national life in which they have not left an indelible mark. Their deep commitment to India’s freedom, their concern for the overall happiness and prosperity of the entire nation, and their lifelong pursuit of excellence have rendered them immortal in the history of India. Undertaking business activities was their inheritance but engaging in public service was their passion. All their actions reflected their forward-looking and creative minds. Theirs was a precious heritage that would be carried forward from one generation to the next.

But before traversing the path to India’s industrialisation, the Marwaris took upon themselves the onus of playing a key role in India’s struggle for independence from the tyranny of the British Raj.

As Indians we can be justifiably proud of the Marwaris from the Shekhawati and Marwar region who left their homeland in pre-independence India, travelled and braved innumerable obstacles to finally emerge as successful traders and businessmen. Their descendants and, indeed, the entire country have much to thank them for.

3 Comments

i WISH TO SUBSCRIBE THE MAGAZINE

i WISH TO SUBSCRIBE THE MAGAZINE. IT IS AN EXCELLENT EFFORT TOWARDS PROJECTING OUR COMMUNITY.

Thank you. Kindly mail us at robert@spentamultimedia.com for subscription inquiries.