The Man Behind the Musician

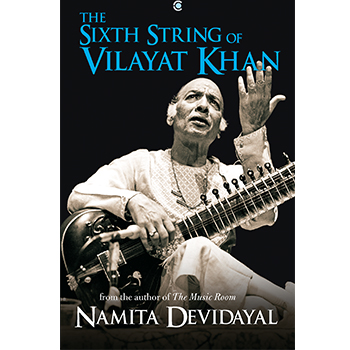

In The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan, author and journalist Namita Devidayal has created an intimate portrait of the man and sitar maestro Ustad Vilayat Khan. Tracing his journey from Gowripur to Kolkata, Delhi, Mumbai, Dehradun and, ultimately, Princeton University, USA, the book focusses on Khan’s music and his mastery over the sitar. It also reveals the musician’s fragmented yet fascinating personality, who also loved cars, cooking and playing cards. Yet, his life was replete with personal and professional conflicts, sensitively expressed through anecdotes that make up much of the book. Devidayal’s past works include the award winning The Music Room and Aftertaste. She also is a trained classical singer.

We bring you a Q&A with the literary sensation, followed by excerpts from the book.

Yes, because of the way in which my first book The Music Room had been received, Vilayat Khan’s younger son Hidayat kept insisting that I’m the best person to write this book. He persisted for more than a year. And I finally agreed, and then there was no going back because the Khansahib’s story was so fascinating.

What kind of research did it take to write The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan and how easy or difficult was it to gather all the anecdotal evidence?

It was quite difficult to gain people’s trust but once they knew I was sincere in my efforts, everyone opened up. It took a lot of patience. I applied my journalistic skills to do some serious detective work into his life! I interviewed people who knew him closely as well as remotely—from his widow to his doggy vet to an American man who became obsessed with recording him.

When you are a biographer, you have to be constantly sensitive to the fact that you are entering—indeed sometimes encroaching—on another individual’s life. Therefore, while I wanted to be as accurate and intimate in my portrayal, I also chose not to write details that I thought would upset those close to him, especially very personal ones. It was a constant juggle, but I think the love and admiration was the underlying current.

The book opens with an interesting story about an onstage duel between Ravi Shankar and Vilayat Khan. How did you come across this anecdotal bit of information?

I had heard this story many times from different sources. After listening to the accounts, I put the scene together because I think it instantly placed him in the larger context of the sitar playing world. Most non-musical readers have heard of Ravi Shankar, but who was this Vilayat Khan? That was the point of that scene and I loved the drama of it.

The book was launched on November 28, 2018 in the gorgeous Royal Opera House in Mumbai. It was the most fitting space, for it was exactly what he would have wanted—a magnificent and beautiful auditorium. His younger son Hidayat played a short concert as a tribute to the book and to his father. I have since been utterly overwhelmed with the response to the book. People love it and I am so grateful for the way it has captured their heart and imagination, and hopefully brought them closer to his music.

EXCERPTS FROM THE SIXTH STRING OF VILAYAT KHAN

1952, Delhi. It had been five years since Independence and India was still in the mood for celebration. Two young string musicians were performing together at the Constitution Club grounds—a sitar player called Ravi Shankar and a sarod player whose name was Ali Akbar Khan. Both were in their early thirties and students of Baba Allauddin Khan, an ambidextrous musician with a goatee, famous for his genius and his temper.

1952, Delhi. It had been five years since Independence and India was still in the mood for celebration. Two young string musicians were performing together at the Constitution Club grounds—a sitar player called Ravi Shankar and a sarod player whose name was Ali Akbar Khan. Both were in their early thirties and students of Baba Allauddin Khan, an ambidextrous musician with a goatee, famous for his genius and his temper.

The concert was part of the Jhankar Festival. There was tremendous anticipation around this particular performance and the music fraternity had been buzzing for days. Ravi Shankar had already astonished the world by creating an orchestra for the new All India Radio. Ali Akbar, who happened to be baba’s son, was emerging as one of the most refined musicians of his generation. Accompanying them that evening were two tabla masters from Banaras, Kanthe Maharaj and his nephew Kishan.

A covered stage had been constructed on the grounds. The musicians walked up, one behind the other, all wearing white. While they were tuning their instruments, a young man in a black kurta and rimless glasses suddenly appeared in front of the stage, clutching his sitar.

He addressed the audience in beautiful Urdu. ‘This stage has so many gorgeous flowers. I would like to add my fragrance by joining my friends Robu-da and Alu-da this evening.’

A murmur of surprise went around the audience. The performance was meant to be a duet. Who was this? Although he spoke poetically, this man had the air of a human detonator. He held his instrument as if it were a weapon, pointing it at phantom enemies. His eyes blazed behind the glasses he wore.

Some recognised him as Vilayat Hussain Khan, the son of Enayat Hussain Khan. A few people started cheering. Baba Allauddin Khan gestured angrily from the front row, trying to stop the duo from becoming a trio, but by then the audience had already expressed its excitement over the intervention and it was too late. The young man jumped onto the stage and the other musicians made space for him.

Baba walked up to the stage and growled at all three: ‘Remember, you are all my children. Play with love and respect.’

It was a formidable stage. Ali Akbar sat in the centre, looking vaguely daunted. On either side of him sat the two sitar players, both strikingly good-looking men with large foreheads suggesting grand destinies. Kanthe Maharaj was on one side of the stage. Kishan Maharaj sat on the other side, kneeling in his distinctive manner, as if he were doing namaz. Two grand Miraj tanpuras at the back and two Chicago Radio mikes in front—it was a picture of perfect melodic symmetry.

In the front row sat the undisputed heads of the music world and Delhi’s wealthiest patrons, including the Shriram–Shankarlal family. The men were dressed in stylish achkans or suits, the women in gorgeous Banarasi silk saris. They rustled. They coughed. The master of ceremonies introduced the musicians.

Ravi Shankar made the customary gesture asking for permission to begin. He then struck the notes of raga Manj Khamaj. He played for a few minutes then turned to Vilayat Khan, giving him the cue. The younger musician played the same riff, but in a more lilting style. They meandered through the alaap for almost an hour, building gradually, thoughtfully, teasing the ma, the raga’s dominant note, the ‘manj’ in the Khamaj.

At some point, it became evident to the audience that a subtle musical duel was taking place.

The Early Years

His first memory of music: the colour yellow. No words. Only sound, sublime. Albert Hall in Calcutta. He was six years old. His father walked onto the stage carrying a sitar, ringlets cascading down either side of his neck, and everyone stood up, even the British governor. The music began, like a giant wave in slow motion, gradually pulling everyone in. Then the picture grew blurry. The child kept falling asleep and waking up, floating between dream and reality, the two spaces linked only by sound. His eyes suddenly opened to loud claps. That’s when he saw a haze of yellow all around.

‘Arre, Vilayat miyan,’ his father said playfully the next morning. ‘My silly, sweet child! That was the colour of Basant, of spring. You saw the raga.’

The Foreign Circuit

Vilayat Khan clearly loved the flavour of the West because it was so different from the politics of music in India. During a radio interview with BBC in London, sometime in the sixties, he was asked to compare the audiences in India with those in Britain and he said, ‘Well, you know, the problem in India is that there is so much ooh-ing and aah-ing; I prefer the quietness of audiences here.’

This was followed by a series of regular trips across Europe for concerts, mostly with Imrat Khan. In 1959, Vilayat was awarded a silver medal at the First Moscow International Film Festival for his music direction in Satyajit Ray’s Jalsaghar.

Portrait of an Older Musician

By the time he was in his sixties, Vilayat Khan’s temper and rancour had become legendary. People almost expected him to begin his concert with a lament against the government or a tangential reference to a certain popular sitar player.

By the time he was in his sixties, Vilayat Khan’s temper and rancour had become legendary. People almost expected him to begin his concert with a lament against the government or a tangential reference to a certain popular sitar player.

Even when he was at the top of his game, he felt a conspicuous disenchantment with the music scene in India. In the late seventies, he had a particularly unpleasant experience with an audience in Bombay. He was performing at Shanmukhananda Hall in support of the Naval Charities. The hall was packed with dignitaries, including Governor Ali Yavar Jung, Admiral Nanda and the singer Kishori Amonkar.

Khansahib was in a great mood, laughing with friends and fans who popped into the green room where he sat making his paan. A woman wearing a headscarf appeared at the door and said a salaam. Vilayat Khan looked up at her and smiled. ‘Tum aa gayi ho.’ You have come. Her eyes smiled back at him, and then she disappeared into the auditorium. She may or may not have been one of the many fireflies who flickered briefly in his life.