The indomitable baron of the fourth estate

For a man who counted among the richest of his time and who also held the power to make or break governments, Ramnath Goenka was unassuming and downright simple. Ever clad in his customary khadi kurta, dhoti and slippers, his life was a perplexing blend of parsimoniousness, Gandhian frugality and total lack of ostentation on one hand, and occasions of unusual generosity and humaneness on the other. Quick tempered, he could be harsh, retributive and critical and also tender and caring. Having pursued lofty causes since his earliest days, here was a man with an unshakable sense of purpose who seemed more concerned about larger issues than things as mundane as family life or the luxuries the money buys. Like a born fighter, he began life taking on the high and mighty and continued crusading against corruption, fraud and misgovernance until old age and failing health got the better of him and laid him to rest on October 5, 1991, at the age of 87.

The birth of a revolutionary

The birth of a revolutionary

Ramnath Goenka was born to a Marwari-Baniya family, originally from Mandawa, Rajasthan, on April 3, 1904, in Darbhanga district, Bihar. His father Seth Jankidas was one of Seth Shiv Manikram’s three sons, the other two sons being Basantlal and Ganpatrai, both of whom died heirless. Having lost his mother very early in life, Ramnath Goenka was adopted by his uncle Basantilal’s widow, who owned estates and a flourishing business left behind by her late husband.

When barely 15, Ramnath Goenka was sent to assist his maternal uncle Prahaladrai Dalmiya’s prosperous fabric merchandising business in Calcutta [now Kolkata]. Later, he was sent to Sukhdevdoss Ramprasad Company [also in Calcutta], then considered the largest firm dealing in yarn. But more than business, it was politics that Ramnath Goenka had on his mind.

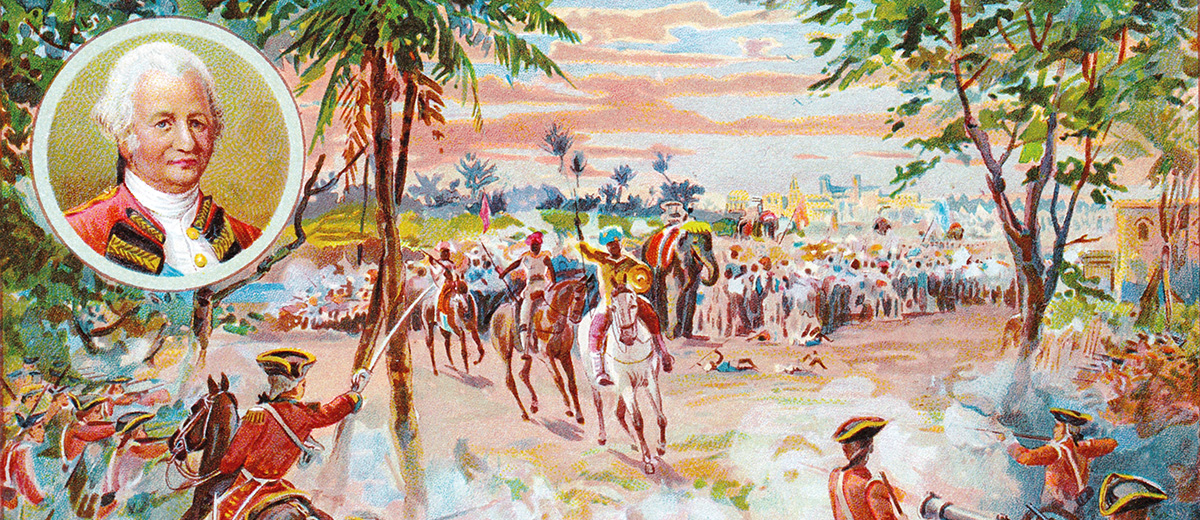

It was a time when the Indian nationalist movement was gathering steam and roused by Gandhiji’s rallying cry for Satyagraha, both young and old were joining the freedom movement in droves. One among them was Ramnath Goenka. Young and impressionable, his nationalistic fervour was intense. He was to soon take part in Gandhiji’s rallies, which inevitably brought him in contact with the Mahatma. Though still in his teens then, his revolutionary bent of mind and dedication to the freedom struggle, combined with a hardcore business outlook could scarcely miss Gandhiji’s attention. One of Gandhiji’s imperatives in those days was establishing a newspaper dedicated to the freedom movement. This exigency, impelled upon Ramnath Goenka by Gandhiji, hugely appealed the latter. But having been imprisoned soon after for subversive activities against the British, his life took a different turn. After his release, concerned about his well being, his worried guardians sent him to Madras [now Chennai] to start a new venture as a representative of the Sukhdevdoss Ramprasad Company. This was in 1922.

The making of a tycoon

The making of a tycoon

In Madras, Ramnath Goenka was appointed dubash (evaluator-cum-investigator) of an English firm, wherein it became his job to assess the credibility of Indian trading firms for British suppliers. Given his sharp business and financial skills, he also traded in stocks and bullion, which helped him amass considerable wealth.

Though it would seem that he had diverted his mind totally to business, deep within the fire of nationalism continued to burn, especially his Gandhi-inspired dream of setting up a swadeshi newspaper. This led him to offer his services to the Hindi Prachar Sabha of Madras, which not only earned him national recognition but also brought him close to leading figures of the nationalist movement such as Jamnalal Bajaj, Lala Lajpat Rai, Madan Mohan Malviya, C Rajagopalachari, Subhash Chandra Bose and Gandhiji. Emboldened, he began taking part in public protests against the British. To win him over, the governor of Madras nominated him to the Madras Legislative Council as a representative of the business community—this was in 1926, when Ramnath Goenka was just 22 years old—but his sentiments clearly lay with the Opposition and in the Opposition he chose to sit.

On cues from Gandhiji, Ramnath Goenka in the meanwhile had purchased debentures of the ailing Free Press Journal of India (Madras) Ltd (which owned The Indian Express and the Tamil daily Dinamani). When conditions deteriorated further for The Free Press Journal, its owner, Swaminathan Sadanand felt compelled to sell off his stake in the company and with that The Indian Express came under Goenka’s control. The year was 1935. The takeover involved a substantial investment, requiring Ramnath Goenka to divest his other businesses. Thereon, he concentrated fully on The Indian Express and Dinamani, even to the point of personally delivering the papers to every village, township and newspaper agent where his papers had a readership. Apart from that, his involvement in writing and publishing the paper, together with his assistant A N Sivaraman, gave a head start to the fledgling daily that was to one day become India’s largest circulated English language newspaper, boasting a countrywide readership through its 14 editions, making Ramnath Goenka one of the most celebrated names of India’s fourth estate.

Fight for freedom

Armed with the might of the pen now, he resumed his attacks on the British government with renewed vigour. Meanwhile Gandhiji launched the Quit India movement (in 1942), which had an apprehensive British government issue a gag order on the press, which entailed pre-censorship of editorial content to suit British ends. But rather than acquiesce, in response, Gandhiji called for all nationalistic newspapers to close down in protest, prompting a seething Ramnath Goenka to unleash a scathing attack on the British by publishing his famous ‘Heart Strings and Purse Strings’ article which decried British attempts to muzzle the press and stifle nationalist thought. The incident marked the beginning of Ramnath Goenka’s lifelong crusade to uphold the freedom of the press. Though it did make an icon out of him and set a certain benchmark for Indian journalism, it was to cost him very dearly later.

India gained independence in 1947. Independence brought about new responsibilities for the Congress Party (whose members primarily constituted the leaders of the Freedom struggle). Given his experience as a member of the Madras Legislative Council, Ramnath Goenka was chosen as a member to the Constituent Assembly of India, the august body entrusted with the responsibility of framing India’s Constitution. It not only brought him closer to the top leaders and bureaucrats of the day but also gave him an in-depth knowledge of the country’s legal and constitutional framework, thereby arming him for the battles he was to later wage against the powers that be.

Business and politics

Business and politics

On the business front, having taken over The Free Press Journal, Ramnath Goenka next set his sights on expansion through a series of takeovers and launches. He proceeded to purchase Andhra Prabha, a Telugu daily, in 1939; the Morning Standard in 1944, which later was converted into the Mumbai edition of The Indian Express; the Indian News Chronicle in 1951, which was converted into the Delhi edition of The Indian Express; and the Gujarati dailies Jansatta and Loksatta, published from Baroda and Ahmedabad respectively, in 1952. Apart from these, new editions of The Indian Express were launched in Madurai, Bangalore (now Bengaluru) and Ahmedabad from the mid-fifties to the mid-sixties. In addition, the The Financial Express was launched in Mumbai, in 1961; the Kannada Prabha (Kannada daily) in Bangalore in 1965; and a new edition of Andhra Prabha in Bangalore, also in 1965.

In the political arena, Ramnath Goenka had until then been on good terms with both Jawaharlal Nehru (India’s first Prime Minister) and his daughter Indira Gandhi. However, trouble started brewing on Nehru’s demise in 1964, when Lal Bahadur Shastri took over as his successor, under whom Indira Gandhi was appointed Information and Broadcasting Minister. Soon there were murmurings of discontent among some members of the party over the appointment. Nevertheless, Ramnath Goenka continued to favour Indira Gandhi and even campaigned for her in the 1966 elections, which brought her to power. But barely three years after she assumed power, trouble reared its ugly head when she (Indira Gandhi) was accused of violating party discipline and expelled from the Congress Party.

It so happened, Indira Gandhi was for following a populist agenda, while her opponents favoured a right-wing agenda. Eventually, these differences split the party into Indira Gandhi’s Congress (Requisition) or simply Congress (R), and the rival Indian National Congress (Organisation) or INC (O). As for Ramnath Goenka, he was dead against a division of the old Congress Party and even advised Indira Gandhi against it. But eventually the duo chose to disagree, and with it Ramnath Goenka fell out with Indira Gandhi.

Yet another political stalwart of the time, who had not taken the division kindly, holding Indira Gandhi’s alleged autocratic ways responsible for it, was Jayprakash Narayan. The duo joined hands in the aftermath of Indira Gandhi winning her second term in 1971, resolving to put an end to her despotism (amid allegations of electoral malpractices) and also fighting poverty, unemployment and the growing frustration and disenchantment among the country’s youth. Jayprakash Narayan went around mobilising the nation’s youth and reaching out to intellectuals, making them aware of the worsening political condition of the country. At a meeting with intellectuals, a resolution was taken to keep them all apprised of developments through a weekly paper called Everyman’s that was to be printed and published by Ramnath Goenka. Also, as opposed to most other media, The Indian Express chose to go anti-establishment, furthering the opposition’s fight to put an end to Indira Gandhi’s regime.

Soon there were youth agitations around the country. There was also the Nav-Nirman movement in Gujarat that saw the Janata Morcha (party) topple Chimanbhai Patel’s established government over charges of corruption. Emboldened by the Gujarat success, a similar movement was in the offing in Bihar as well. To quell the spreading unrest, the government resorted to force which further vitiated the atmosphere and brought most of the Opposition parties together under Jayprakash Narayan. Feeling threatened by the ever-growing ranks of the Opposition, Indira Gandhi then took the ultimate step of suspending the Constitution and declaring Emergency on June 26, 1975.

The Emergency and its aftermath

The Emergency brought about a fresh round of oppression and repression, with renewed vigour and intensity. Inevitably, it brought Ramnath Goenka in the cross-hairs. What followed was intimidation and unabated harassment for almost two years that was enough to bring even the doughtiest to their knees. But not Ramnath Goenka; he was made of sterner stuff.

The persecutions mostly came from the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. There were repeated attempts to take over The Indian Express, there were threats of arrest under the dreaded Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA), there were charges of corporate malpractices, charges of evasion of income-tax, attempts to dictate editorial policies, demands for removal of key editors of the group, strict censorships of the newspapers, non-patronisation of the papers (by secretly suspending release of government advertisements), discontinuation of power supply so as to impede normal functioning of the press, etc.

As and when expedient, Ramnath Goenka took judicial recourse to counter these charges. But at a point, when no amount of reasoning, litigations or third party mediation would work, he threatened to disclose the contents of certain letters written by Indira Gandhi and Feroze Gandhi in the good old days that were in his possession. He also issued a detailed letter to P N Dhar, secretary to the Prime Minister, writing about the Information Ministry’s systematic attempts to cripple the group. These measures, among others, produced the desired result and the persecutions stopped. But more harassment was to come.

As the Emergency progressed, there was growing eagerness among the populace for restoration of democracy. Eventually, Mrs Gandhi felt compelled to lift the Emergency in March 1977. Once the Emergency was withdrawn, Ramnath Goenka went on to claim his pound of flesh by publishing a series of exposes on the excesses committed by Indira Gandhi and her son Sanjay Gandhi during the Emergency in The Indian Express. Subsequently, she was voted out of power in the 1977 elections. But the sparring resumed after she came back to power in 1980, and then there was some more of it when Rajiv Gandhi assumed power in 1984, after Mrs Gandhi’s assassination.

A born fighter, through all these trials and persecutions, a beleaguered Ramnath Goenka resolutely held his own. Buckle he did, as anyone in his shoes would, but he never gave up the fight. This is because his life revolved around three great passions for which he was willing to go to any extent: the love for the nation and democratic values, the love for the Indian Express Group which he had singlehandedly built from scratch and love for upholding the freedom of the press. Consequently, more than financial considerations, the raison d’être of his papers was serving as mediums of communication that reflected the dictates of a patriotic and strongly principled man, who was willing to stake everything for what he believed was right.

Fight with the Ambanis

Perhaps these very traits also explain his famous fights with his one-time friend Dhirubhai Ambani of Reliance Industries (it actually was the fallout of an ongoing corporate war between Dhirubhai Ambani and Nusli Wadia of Bombay Dyeing). Possibly India’s very first corporate war, it was to later take political overtones and snowball into a major crisis.

It so happened that both Bombay Dyeing and Reliance Industries were aspiring to foray into the promising polyester industry for growth, for which di-methyl terephthalate (DMT) was a vital raw material. To source this raw material, Reliance Industries was believed to have manipulated the system—given Dhirubhai Ambani’s close links with politicians and bureaucrats in Delhi—which supposedly helped him derail Bombay Dyeing. This led to an all-out war between the two business houses. Their common friend, Ramnath Goenka, tried time and again to reconcile them, but in vain. Eventually, the war spilled on to the media with The Indian Express publishing a series of exposes against Reliance Industries. Articles were also contributed by Maneck Davar, the editor of Marwar, who then was an independent journalist with the Express Group. There were allegations of Reliance Industries employing unfair trade practices to reap profits and the government not doing enough to penalise them.

Family life

Family life

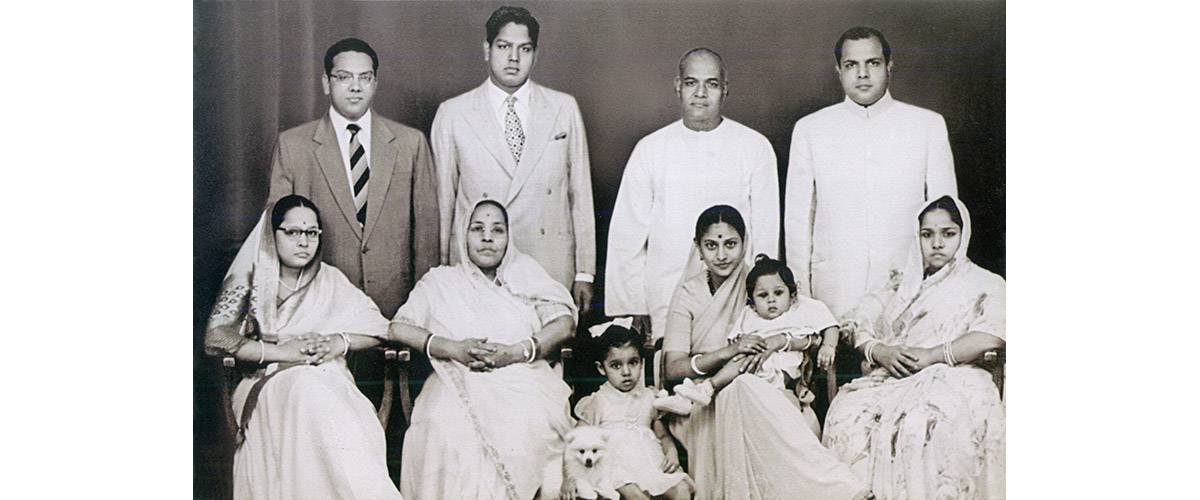

Ramnath Goenka was married to Mungibai early in life, with whom he had three children: son Bhagwandas Goenka (married Saroj Jain), daughters Krishna Khaitan (married to Ajay Khaitan) and Radha Sonthalia (married to Shyam Sunder Sonthalia). Sadly, Bhagwandas Goenka, heir-to-be of the Express Group, died rather young, leaving a void with no male heir to take over the business. In his desperate search for a successor, Ramnath Goenka then adopted his daughter Krishna Khaitan’s son Vivek Khaitan (scion of the Kolkata-based Khaitan business family that owns Williamson Magor and McLeod Russell, among other companies). Thus, grandson, Vivek Khaitan, became his adoptive son, who subsequently changed his name to Vivek Goenka. He (Vivek Khaitan) currently holds the reins of a part of the former Indian Express Group (constituting the Bombay-based part of the business), together with his son Anant Goenka.

After Ramnath Goenka’s death in 1991, a bitter property dispute broke out between his children. Finally, an out-of-court settlement was reached, where Vivek Goenka received control of the Mumbai-based part of the business (now called The Indian Express Group, with seven north Indian editions of The Indian Express), and Manoj Kumar Sonthalia, son of Radha Sonthalia, getting control of the Madurai-based part of the business (now called The New Indian Express, which holds the nine South Indian editions of the paper). Both the houses, however, continue to grow and take Ramnath Goenka’s legacy forward, cherishing and upholding all the values he stood for.