Strength of a Woman

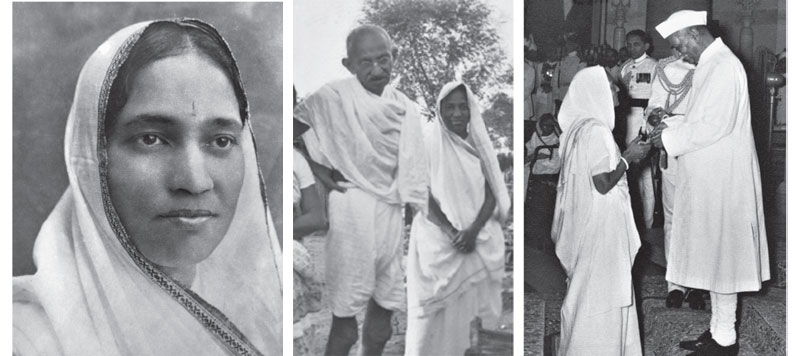

A true Gandhian, a staunch nationalist, a social reformer and Padma Vibhushan awardee, Jankidevi Bajaj worked tirelessly to overcome societal evils and contributed immensely to the country’s struggle for freedom. The English translation of her autobiography, My Life’s Journey, traverses her life through witty, poignant and, often, humorous anecdotes.

To read jankidevi bajaj’s autobiography is to get an interesting viewpoint of some of the most important moments in the history of India, from the Civil Disobedience Movement and Dandi March, right up to the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi.

Jankidevi was born into a wealthy family in Jaora, Madhya Pradesh, in 1893, and was married at a young age to Jamnalal Bajaj, the heir of the prosperous Bajaj family of Wardha. Like her husband, she too chose to renounce a life of luxuries, in favour of one that adhered to the Gandhian tenets of simplicity and humility. As a social reformer, she advocated the use of khadi, contributed to the abolishment of purdah and revolted against untouchability.

Sensitively translated from Jankidevi’s original autobiography, Meri Jivan Yatra, the English translation by Sudeepta Vyas is compelling and inspirational. Spanning 400 pages, it is dense with prominent of a woman facts, names and years, while a glossary at the end lends context to unfamiliar terms. Jankidevi’s simplistic style of storytelling makes the book a fast-paced read, offering more than just a glimpse into the life of someone who was influenced by the likes of Gandhi and Vinoba Bhave, someone who ushered social change, someone who was once imprisoned, and yet was a caring homemaker and mother of five.

A touching foreword by her grandson Rahul Bajaj, Head of Bajaj Group, and a preface by Bhave that was previously published in her original autobiography, bring to the fore heart-warming moments they shared with the strong-willed Jankidevi. Fittingly, the book was launched on her 125th birth anniversary earlier in January this year, at the 26th IMC – Ladies’ Wing Jankidevi Bajaj Puraskar 2018.

We bring you excerpts from the book.

Excerpts From My Life’s Journey

Patriot and social worker Jankidevi, after giving up all her jewellery and fine silks at the age of 27

Excerpt

We lived in a village named Jaora. This area was under Muslim rule and we often had a Muslim band play at our family weddings. The entire town turned out in hordes to watch them. Muslims of the area had immense respect for my father.

My father lived a life of simplicity and purity. His business defined him as did his honesty and simplicity. He made profits without greed and sold off his produce for a small profit. As a result, wealth flowed freely into our house as long as he lived.

Father owned an opium business. The labourers would bring home pots of opium juice from the fields that would be stirred till thick and shaped into balls. Our barns were filled with opium balls worth lakhs of rupees.

Man’s greed can bring him down very soon. After my father, the family often faced the wrath of loss due to bad business practices. My father believed in small profits that paid off big dividends.

After my marriage, when it was time to leave my father’s house, he advised, “Beti, you are about to set foot in a new house. Make sure you put on your best behaviour all the time. Answer politely when spoken to.”

His death was as peaceful as the life he lived. His day began with writing letters till 11 am. He then had a bath and felt some discomfort while tying his dhoti. He rested in his room while the doctors were summoned from faraway Indore to have a look. It was all in vain. At 7 pm he passed away. They say his soul left his body from the topmost part of his head. Such a death is the privilege of a true saint or mahapurush.

At the time of my father’s death, I was around 11 years.

Excerpt

Bajajwadi, Wardha – The National Guest House

I was all of 13 years. We had a visitor at home. He had a golden belt tied below his waist. I was impressed. I thought if we had a few golden waist belts at home, Jamnalalji would look grand in them. I insisted he should wear one. He said gold was a form of God. How could one wear it below the waist? That got me thinking. What was I to do? I was not one to question at that age. I believed everything that was told to me. What was I to do with the waist belt I wore? I did like to wear it though. It was quite a highlight for me after my engagement ceremony and an important piece of jewellery for a woman. I took care with my dressing just as my mother. After some deliberation, I got rid of my belt. In the days ahead, Jamnalalji referred to the waist belt at the Agrawal congregation, and henceforth it was banished from the household.

One fine day, it was time to give up all my ornaments, not just the waist belt. Gandhiji had exhorted us to give up all ornaments. I got this message via a letter from Jamnalalji. If he had asked me to do this in person, I would have put up a defence, but a letter from Gandhiji was gospel and how could I refuse? Every word in the letter was a command. One after another, the ornaments came off. These words echoed in my mind ‘…gold breeds greed and jealousy. We covet it and fear losing it and being robbed. It irritates the skin and causes bad odour. Besides, it does not provide any interest on capital…’ These words had a lasting effect on me.

Jankidevi inspiring villagers with her speech during

the Rajasthan koopdan yatra

Excerpt

I perceived the ghunghat as an expression of bashfulness. The ghunghat was much glorified. It suited me to keep my plain looks covered. But when I learnt the significance of relinquishing this veil, I found the courage. It wasn’t easy. I carried the practice at Ahmedabad Congress session. I finally gave it up at the Sabarmati Ashram.

Once I found my freedom from the ghunghat, I was keen to see other women see reason as well. I would coax them to shed their veils in open forums. This soon turned into an obsession. Many women found the courage and gave up the practice. Some reverted to the ghunghat as they feared the wrath of their family and society.

Twenty-two years ago, a Marwari women’s convention was held in Calcutta. I was elected as the president. Bapuji addressed us and made a moving plea to banish the practice of ghunghat.

Jankidevi Bajaj with Gandhiji

Excerpt

Soon after the closing down of the Vile Parle station, I moved to Matunga and was a guest at Keshavdevji Nevatia’s house. One day, Kasturbaji along with Goshibehen, Perin-behen and a few others came over. They informed us that women were not being spared and arrested at rallies. I was advised to go elsewhere to avoid going to jail. They wanted me to continue our work for the Freedom Movement and that was hard to do within the four walls of a prison. They proposed I should leave for Calcutta to give momentum to the protests around boycotting of Western clothes.

This news travelled to Jamnalalji’s prison. He was unhappy about being in a position where he couldn’t contribute much while his fellow freedom fighters were facing hardships in the outside world. He often wrote letters to encourage their work. In one of his letters to me, he wrote that I was known as Jamnalalji’s wife, but when he would be released from jail, he would be known as Jankidevi’s husband. He made me feel proud of my work. I did a substantial amount of public speaking and my name was bandied around in the newspapers.

Jankidevi Bajaj receiving Padma Vibhushan from the President of India, Dr Rajendra Prasad

Excerpt

Jamnalalji may have had a premonition about his death. All of us, however, were clueless and this came as a huge shock. Bapu was deeply affected and felt his absence in a big way. But he had the mental makeup of a yogi. He quickly recovered from his grief and began looking at ways to manage Jamnalalji’s social work.

Bapu organised a meeting on the 12th day of Jamnalalji’s demise. He requested friends, followers and well-wishers to continue the noble work left behind as a true homage to Jamnalalji. According to Bapu, this was an appropriate way to offer peace to the departed soul.

The huge blow made me impassive. I felt a sense of detachment. I was constantly reminded of Jamnalalji’s life mission and vision and began to assimilate these into my mind. I was ready to walk in his steps. Our family was deeply influenced by Bapu’s philosophy. I give all credit to him to whatever I have achieved so far. Bapu also believed I should dedicate each moment of my life to Jamnalalji’s work. He offered me the responsibility of goseva. I was keen to do this, but hesitated to become the president of the Goseva Sangh, as Bapu wished. He offered me the help of Vinobaji, and Ghanshyamdasji Birla as vice-president. No one could refuse Bapu and soon we all agreed to our positions and responsibilities.

Excerpts from ‘My Life’s Journey’ by Jankidevi Bajaj shared here with the permission of Jaico Publishing House

Jankidevi Bajaj with Vinoba Bhave at Pavnar Ashram

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi presenting a copy of Samarpan Aur Sadhana – a commemorative volume on Jankidevi Bajaj on her 80th birthday

Excerpt

I was getting wide recognition in the country as Jamnalalji’s wife. However, I was not as largehearted as him. I was known for my stinginess. It was a way of life with me and I found it very hard to kick this habit. I had once asked Rahul (Rahul Bajaj, grandson, Kamalnayan’s son) about his memories of me as a child. He remembered the time I had stopped Jamnalalji from buying him some sweet treats in Gopuri. This was his precious memory of his grandmother as a four-year-old! Well, this was me! I liked to hoard small and irrelevant things. I wasn’t worried about larger items as I knew someone would look after them. I found it easy to part with a hundred rupee note but couldn’t let go of a few annas (loose change).

Bapu was also known as the King of Stinginess. The difference between us was huge. He did it with elegance. He recycled most things such as envelopes and paperclips. He wrote back messages of good wishes on the same invitation card that was sent to him. Bapu’s acts of miserliness appeared graceful while mine appeared plain stingy. People admired Bapu for what he did while I gained a reputation of being a miser. Bapu, however, admired me for this quality. It takes a miser to understand another! I was fortunate to be awarded a certificate of stinginess from him.

My Life’s Journey by Jankidevi Bajaj Translated by: Sudeepta Vyas Publisher: Jaico Publishing House Price: R499/-