Of Borders and Boundaries

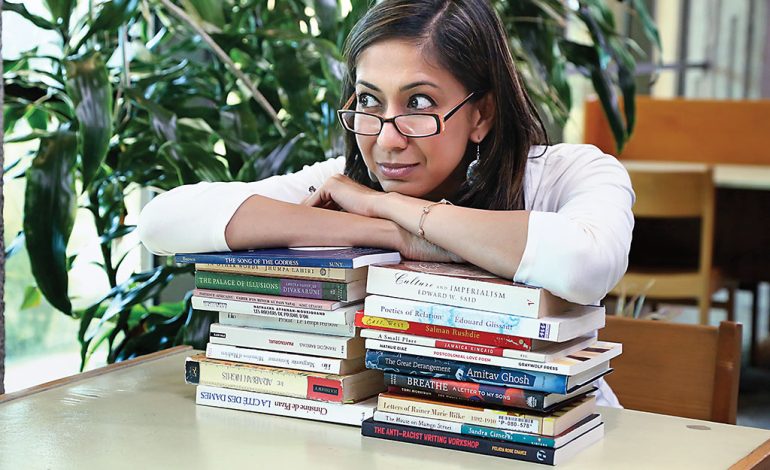

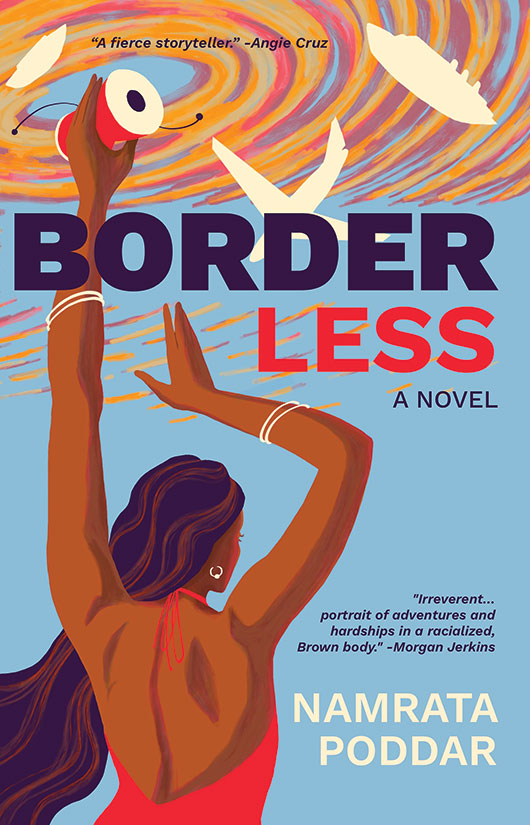

Born in Kolkata and raised in Mumbai and lived in France and Mauritius, fiction and non-fiction writer Namrata Poddar is currently based in Los Angeles. Her debut novel, Border Less puts the limelight on two contradictory but irrepressible human urges: to settle and to move. A finalist for The Feminist Press’s Louise Meriwether Prize, the book follows the journey of Dia Mittal, an agent at an airline call centre in Mumbai whose search for a better life takes her to the United States. The book centres desert and coastal spaces, and draws inspiration from Sanskrit literature, especially mythological stories from the Puranas to the performative, architectural and visual storytelling traditions of Rajasthan, including dance, miniature paintings, and Marwari havelis of the Thar Desert. Some parts of her novel also have references to Marwari art and culture, Marwari merchants, trade caravans of the Silk Road, and migration and movement. In this interaction with MARWAR, she talks about the inspiration behind the book and her love for writing. Over to Namrata.

Tell us about your debut book Border Less A Novel, the finalist for Feminist Press’s Louise Meriwether Prize. Tell us about the book.

Border Less started in 2004 when I took a year-long break from my PhD programme in French Literature at UPenn (University of Pennsylvania) and returned to Mumbai to rethink my choices with a world of books. At UPenn, I was training to become a literary critic, but fiction writing is something I yearned constantly to pursue. I wanted to write for a much broader audience, especially the community I grew up with, including young middle-class women of Mumbai. So in that year off from grad school, I started writing regularly in a notebook and allowing myself the permission to take the risk of simply following my heart. As I continued writing, one of the first chapters of the book came to me, a fictional scene in a crowded ‘ladies special’ train that I used to take regularly over my commute to college in Mumbai. Soon, other characters started appearing—people from the community I belonged to when living in different parts of the world.

Of Borders and Boundaries

The book is divided into Roots and Routes. What parts are you connected with?

I feel connected to both parts of my book. I feel close to my Rajasthani roots because I grew up with a strong presence of Marwari culture in my mother and my father’s family, but neither my parents nor my sister and I have truly lived in our roots. I have lived in coastal cities all my life—Calcutta (now Kolkata) where I was born, Bombay and Mumbai where I was raised, parts of France, Mauritius or the United States where I have lived thereafter, including my current home in Huntington Beach that is in Greater Los Angeles area.

The book’s narrative has references to Marwari art and culture. Can you elaborate?

I am a Marwari with roots in the Thar Desert’s Shekhawati region where the Poddars have enjoyed a strong, historic presence that goes back to the Silk Road days and its history of trade, if not earlier. The havelis of Shekhawati with their rich fresco art are also considered the world’s biggest open-air gallery, and I found the art depicted on Marwari homes to be highly avant-garde for the time. One of my biggest motivations was to see in English literature coming out of both South Asia and the West the presence of a Marwari culture, and deserts at large, from an ‘insider’s’ perspective and not through clichés. Personally too, in both Indian and American academia, I have faced consistent prejudice by upper-caste academics against Marwaris and the ‘baniya’ community at large that are seen to not possess any real culture, Brahmins who would remind me how, as a Marwari, I was not capable of becoming a serious artist. Writing Border Less was one way of combating these clichés; it was a way to show how the Thar Desert has always been a rich repository not only of culture but also of histories of migration and cross-cultural contact.

Does the story of Dia have reflections from your life?

Migration is a theme that unites my work of two decades—teaching, research and the writing of fiction and nonfiction. It is an experience that hugely defines my life, and as much, my communal history and identity. So yes, Dia’s story as does the story of almost every other character including her Marwari family in Mumbai or Indian- American family and friends in California are defined by migration.

Did being a Marwari help you in tracing the culture while writing the narrative?

I grew up with Marwari culture and traditions, so writing did not help me trace my culture, but tracing a Marwari culture into the space of writing was very important.

How much of the Marwari culture have you adapted in your life?

I did change homes often in my life. And I grew up with Marwari culture and traditions that are still a part of my life. As for how much of a Marwari is within me, I don’t know how to quantify this specific part of my transnational, multicultural identity.

Poddar doing her yoga practice

How did you get the inspiration for storytelling?

My first professional publication was in 2008, a book review I published for an Indo-Caribbean writer’s novel in a reputed trilingual academic journal. Since then, I’ve been writing and publishing consistently but my debut novel, Border Less, was released first for the North American market in March 2022. Inspiration toward storytelling and the literary arts is all over in my family and my community. My mother is a retired academic and very meticulous in her use of language; my father is a musician whose love of Indian classical music was all around me when I was growing up; my paternal grandfather loved both music and language and could be often found loitering around at home with different editions of the English dictionary; my maternal grandfather held a senior position for a reputed newspaper; my father-in-law, a former academic has published books in the U.S. on Kabir’s poetry and a history of Gujarati migration to the U.S., my motherin- law organises and directs plays inspired from Indian epics and mythology for the Gujarati American community in Greater Los Angeles; my sister and my paternal grandmothers are incredible repositories of Marwari lore and oral stories. I feel very fortunate to be immersed in different traditions of South Asian storytelling when growing up in Bombay, although when it comes to formal training, I did return to graduate school after my doctoral and postdoctoral education in literature to get a Master’s in Fine Arts in fiction writing from Bennington Writing Seminars in the U.S.

You are a writer, editor, with a PhD in French Literature.

To be a brown woman writer living and writing in the United States in the 21st century often means you are multitasking and wearing different professional hats at any time, unless you come from generational wealth and don’t need to think about paying your monthly bills or saving toward retirement.

Tell us about your other passions in life.

Food has always been a big love in my family, in my mother’s and father’s family in Mumbai and Kolkata, in my Californian in-law’s family too. I imagine I picked up this love of food from my loved ones from a young age. For those of us who migrated to another country, food becomes an important way to stay connected with one’s roots. As for yoga and meditation, my Nanaji introduced me to the Bhagwad Gita and translations of and commentaries on it in English in my early teenage. That was my first serious introduction to yoga and its philosophy as Krishna shares it with Arjun on the Kurukshetra. Postural yoga or asanas and pranayamas came later in life, when I was a college student, as did the love of meditation which I see as an extension of my love of imagination and day-dreaming. I have been meditating since I was 18, and what began as a love of going within, has evolved into a steady discipline that is now my biggest anchor in life—a way to navigate our unequal world with too many historic wounds that await our collective healing.