From Traders to Business Tycoons

From Traders to Business Tycoons

Marwaris, without doubt, are the most prosperous business community in India. Though their story has been told and retold, there are few publications that have better chronicled their evolution from desert dwellers to industry leaders than The Marwari Heritage. Authored by Dr D K Taknet and published by International Institute of Management and Entrepreneurship (IIME), Jaipur, the well-researched 512-page tome is not just a readers’ delight but also a visual treat and is a must-have for business historians, researchers, scholars, libraries and Marwaris.

Marwaris, without doubt, are the most prosperous business community in India. Though their story has been told and retold, there are few publications that have better chronicled their evolution from desert dwellers to industry leaders than The Marwari Heritage. Authored by Dr D K Taknet and published by International Institute of Management and Entrepreneurship (IIME), Jaipur, the well-researched 512-page tome is not just a readers’ delight but also a visual treat and is a must-have for business historians, researchers, scholars, libraries and Marwaris.

Text ✲ Joseph Rozario

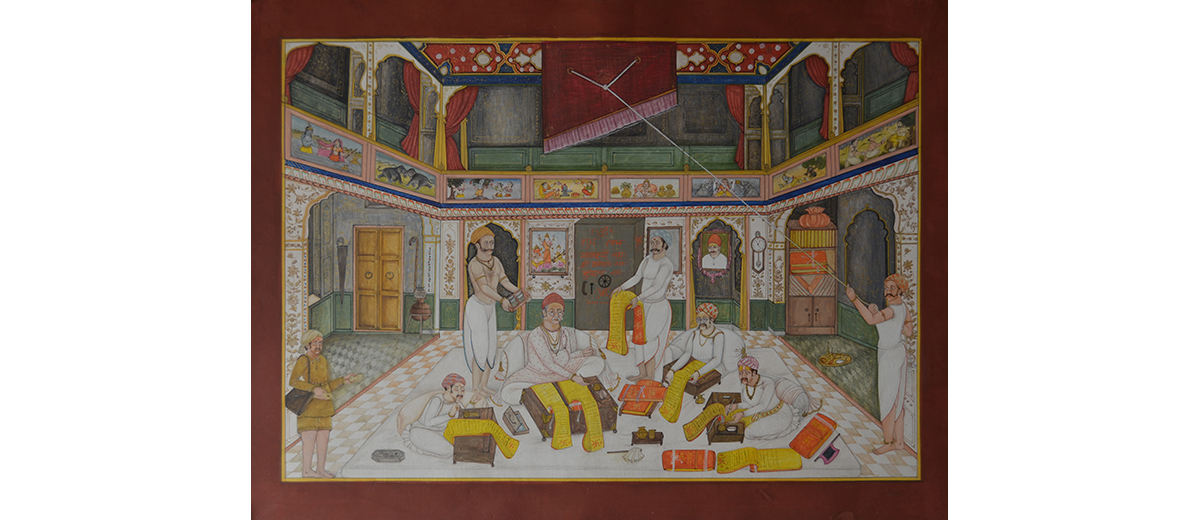

Pictures ✲ Courtesy Business History Museum, IIME

The story of the evolution of Marwaris as a business community traces back to India’s oldest mercantile community, the Vaishyas, who traditionally have been involved in trade, commerce and moneylending since times immemorial. Under the Mughals, particularly during the reign of Emperor Akbar, some Vaishyas from Rajputana started migrating to Bengal, together with Rajput warriors who were sent to Bengal as part of the emperor’s army. While assisting the army with supply of food, arms and ammunition, in their quest to grow, they started to set up their own businesses alongside. As they prospered, their numbers multiplied and so did their successes, triggering waves of migrations from Rajputana to Bengal. The development of Bombay (now Mumbai) and Madras (now Chennai) as port cities took other branches of Marwari traders to the west and south simultaneously. Bound together with a common purpose and a spirit of kinship, they faced trials and tribulations in lands and cultures alien to them, their desert backgrounds helping them to face every challenge with courage and fortitude, never losing their faith in their ability to win. Some of their more successful brethren went on to hold important positions as ministers, advisors, financiers and diwans, fuelling further growth for the community. Their riches spilled on to social welfare initiatives, giving the country some of its earliest philanthropists. The freedom struggle brought out the best of their bravery and martial character with many courting imprisonment and even laying down their lives for the nation.

The story of the evolution of Marwaris as a business community traces back to India’s oldest mercantile community, the Vaishyas, who traditionally have been involved in trade, commerce and moneylending since times immemorial. Under the Mughals, particularly during the reign of Emperor Akbar, some Vaishyas from Rajputana started migrating to Bengal, together with Rajput warriors who were sent to Bengal as part of the emperor’s army. While assisting the army with supply of food, arms and ammunition, in their quest to grow, they started to set up their own businesses alongside. As they prospered, their numbers multiplied and so did their successes, triggering waves of migrations from Rajputana to Bengal. The development of Bombay (now Mumbai) and Madras (now Chennai) as port cities took other branches of Marwari traders to the west and south simultaneously. Bound together with a common purpose and a spirit of kinship, they faced trials and tribulations in lands and cultures alien to them, their desert backgrounds helping them to face every challenge with courage and fortitude, never losing their faith in their ability to win. Some of their more successful brethren went on to hold important positions as ministers, advisors, financiers and diwans, fuelling further growth for the community. Their riches spilled on to social welfare initiatives, giving the country some of its earliest philanthropists. The freedom struggle brought out the best of their bravery and martial character with many courting imprisonment and even laying down their lives for the nation.

With their exceptional entrepreneurial and financial acumen and their single-minded pursuit of success, Marwaris today have virtually conquered every sphere of Indian industry, and many have gone beyond to make their presence increasingly felt in the global forum. They have generated wealth for the community and the nation in the process, ushering progress, prosperity and modernity and have contributed generously to philanthropic initiatives. In the areas of art and culture too they have made huge strides, enmeshing themselves in the social, cultural and economic fabric of the country in the process.

With their exceptional entrepreneurial and financial acumen and their single-minded pursuit of success, Marwaris today have virtually conquered every sphere of Indian industry, and many have gone beyond to make their presence increasingly felt in the global forum. They have generated wealth for the community and the nation in the process, ushering progress, prosperity and modernity and have contributed generously to philanthropic initiatives. In the areas of art and culture too they have made huge strides, enmeshing themselves in the social, cultural and economic fabric of the country in the process.

This incredible journey from a forbidding terrain to earning name, fame and fortune in distant lands has been captured in the most comprehensive and insightful manner in The Marwari Heritage. A readers’ delight and a pictorial treat, the book brings together extensive research, hundreds of rare photographs, sketches, artifacts and rare documents that weave together an amazing story of names, lives, interesting tidbits, inspiring profiles and fascinating vignettes.

We bring you excerpts from the book. ✲

Excerpts from The MARWARI HERITAGE

Excerpt

Though based in Rajputana, the Vaishyas had for centuries traded in northern India, though some migrated elsewhere. After the advent of the Mughals in 1525, they began migrating to Bengal in 1564. The then ruler of Bengal, Suleman Kirani, continually beset by domestic wrangles, accepted the overlordship of Emperor Akbar. In return, Akbar sent a contingent of Rajput troops under Raja Man Singh to assist him. The modikhana (supply of food, arms and ammunition) was managed by the Vaishyas of Marwar (Jodhpur), who, with their business skills, expanded their business in Bengal. They invited their kin from Rajputana to assist them. In Bengal, they were popularly known as the Vaishyas.

Though based in Rajputana, the Vaishyas had for centuries traded in northern India, though some migrated elsewhere. After the advent of the Mughals in 1525, they began migrating to Bengal in 1564. The then ruler of Bengal, Suleman Kirani, continually beset by domestic wrangles, accepted the overlordship of Emperor Akbar. In return, Akbar sent a contingent of Rajput troops under Raja Man Singh to assist him. The modikhana (supply of food, arms and ammunition) was managed by the Vaishyas of Marwar (Jodhpur), who, with their business skills, expanded their business in Bengal. They invited their kin from Rajputana to assist them. In Bengal, they were popularly known as the Vaishyas.

Despite the fact that the Marwaris originated from Marwar in erstwhile Rajputana, the community later made its presence felt in every corner of India, providing a new impetus to the country’s social and economic development. Its tremendous socio-economic contributions to both pre- and post-Independent India have been widely celebrated and lauded. The word Marwari, as it is recognised today, came to encompass all those who resided in Rajputana, Haryana, Malwa and areas adjacent to them. They followed a common culture and lifestyle and spoke a common language, irrespective of whether they themselves or their ancestors were settled in any other part of India or abroad. Initially, the term Marwari was used for the business class alone, but gradually, all the castes linked to traditional Rajputana culture embraced the term. Consequently, the Marwaris included not only the Agarwals, Maheshwaris, Oswals, Khandelwals, Porwals and Saraogis, but also the Brahmins, Rajputs, Jats, Malis, Muslims, Harijans and others who formed part of the cultural heritage of Rajputana. They comprised not only businessmen and industrialists, but also professionals, the service class and even the labour classes.

Despite the fact that the Marwaris originated from Marwar in erstwhile Rajputana, the community later made its presence felt in every corner of India, providing a new impetus to the country’s social and economic development. Its tremendous socio-economic contributions to both pre- and post-Independent India have been widely celebrated and lauded. The word Marwari, as it is recognised today, came to encompass all those who resided in Rajputana, Haryana, Malwa and areas adjacent to them. They followed a common culture and lifestyle and spoke a common language, irrespective of whether they themselves or their ancestors were settled in any other part of India or abroad. Initially, the term Marwari was used for the business class alone, but gradually, all the castes linked to traditional Rajputana culture embraced the term. Consequently, the Marwaris included not only the Agarwals, Maheshwaris, Oswals, Khandelwals, Porwals and Saraogis, but also the Brahmins, Rajputs, Jats, Malis, Muslims, Harijans and others who formed part of the cultural heritage of Rajputana. They comprised not only businessmen and industrialists, but also professionals, the service class and even the labour classes.

However, it was later felt that by limiting the definition of a Marwari merely on the basis of geographical, linguistic and cultural traditions, the unique image of the community was being undermined. The community boasts a glorious past replete with countless examples of ceaseless struggle, courage, discipline, perseverance, humility, tolerance, compassion, foresight, dedication, risk-taking ability and above all, self-confidence.

Excerpt

Adverse Impact of British Rule

Adverse Impact of British Rule

By 1818, all the princely states of Rajputana had entered into treaties with the British, with the latter assuming responsibility for the formers’ security. Though this reduced the expenditure of the princely states on the army, it was a blow to local businesses dependent on the army. In the meantime, the British gained complete control over the principal trading commodities of Rajputana such as salt, opium and cotton. The defective octroi policy of the British resulted in the escalation of the cost of goods exported to the British Indian states. This made it necessary for the Marwaris to start their business in the British-protected trading centres to avoid the increase in the cost of their goods owing to the excessive octroi levied elsewhere.

The British gradually established a complete monopoly over foreign trade in India. The Charter Act of 1813 gave British traders complete freedom of access to trade in India; consequently, they set up their own offices in Bombay and Calcutta, the two major Indian ports. They did, however, need a large number of agents to procure raw material from India and to sell goods manufactured in Britain. As the traders of Rajputana had no source of livelihood left, they were forced to make the best of available opportunities and became the agents and banias of the British traders. They had begun to feel that it was better to conduct business in pardesh, if they could not earn money by persevering in their own desh.

Excerpt

Spread in Prosperity

From 1860 onwards, massive Marwari migrations took place towards east India. By 1911, there were 15,000 Marwaris in Calcutta and 75,000 in Bihar, Orissa, Bengal and Assam. They established their dominance in the field of indigenous banking soon thereafter. The banias became indispensible to British cotton cloth-importing firms from 1870 to 1900. The Marwari merchants controlled the opium market even before 1860. Marwari merchants entered the jute trade in 1870, and by 1914 trade was controlled predominantly by them. During the First World War, the control of key speculative markets, import of cotton cloth and the jute trade resulted in war profits, which enabled some Marwaris to enter the industrial sector.

From 1860 onwards, massive Marwari migrations took place towards east India. By 1911, there were 15,000 Marwaris in Calcutta and 75,000 in Bihar, Orissa, Bengal and Assam. They established their dominance in the field of indigenous banking soon thereafter. The banias became indispensible to British cotton cloth-importing firms from 1870 to 1900. The Marwari merchants controlled the opium market even before 1860. Marwari merchants entered the jute trade in 1870, and by 1914 trade was controlled predominantly by them. During the First World War, the control of key speculative markets, import of cotton cloth and the jute trade resulted in war profits, which enabled some Marwaris to enter the industrial sector.

In central and western India, apart from the incidental investments of a few major banking firms, most of the available profit from trade and moneylending was invested in land. The Bombay community’s Shekhawati component gained a respectable position in speculative markets, especially stocks and cotton, along with trade in opium, cloth and cotton. However, vigorous competition, especially from various Gujarati commercial groups, did not allow them to achieve as dominant a position as in Calcutta. Before the First World War, a few Marwari merchants had been instrumental in setting up mills for others in Bombay. After the War, however, several started mills of their own. Similarly, in Hyderabad and Indore, war profits enabled the merchants to freely construct cotton textile nd carpet mills.

In central and western India, apart from the incidental investments of a few major banking firms, most of the available profit from trade and moneylending was invested in land. The Bombay community’s Shekhawati component gained a respectable position in speculative markets, especially stocks and cotton, along with trade in opium, cloth and cotton. However, vigorous competition, especially from various Gujarati commercial groups, did not allow them to achieve as dominant a position as in Calcutta. Before the First World War, a few Marwari merchants had been instrumental in setting up mills for others in Bombay. After the War, however, several started mills of their own. Similarly, in Hyderabad and Indore, war profits enabled the merchants to freely construct cotton textile nd carpet mills.

Within a short span of time between 1857 and the end of the First World War in 1918, a small group of Marwaris in Calcutta, numbering fewer than 15,000, started trading from the port. They gradually made further inroads and eventually launched some of the first major Indian-owned firms that manufactured indigenous goods in eastern India and traded in those goods.

Excerpt

The Privileged Class

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the Marwaris became so powerful that the rajas had to consider their views before taking any decision. If the raja ignored the traders’ interests, this provoked mass resentment and protests, and the raja usually had to modify his decree. Maharaja Fateh Singh of Udaipur had to withdraw his decision to hike the customs duty on the export of opium under pressure from the traders. In 1921, the Maharaja of Jodhpur had to ban the import of sugar into the state because the local sugar traders were opposed to it. Bikaner state had to withdraw its decision to levy income tax in 1941 when the traders of Sardarshahar, Churu and Sujangarh protested and the Marwari Chamber of Commerce, Calcutta, passed a resolution against it. Thus, the business community that had been persecuted under feudalism in the eighteenth century, succeeded in wielding great clout with the rajas and jagirdars in the twentieth century on the basis of its newly acquired economic power. The Marwaris had truly earned their place in the sun.

Excerpt

Succession of Arrests

The political ambition of achieving self-rule had by now become the main aim of the Marwaris and with Jamnalal’s imprisonment, several others, including Rameshwar Jajodia, Hiralal Singhi, Puranchand Saraf, Sohanlal Agarwal, Ramgopal, Laxminarayan Mundra, Prahlad Kedia, Badrinarayan Gadodia, Shreenivas, Babulal Makharia and Shivchand Gupt went to jail.

In Bombay, as well as in other parts of the country, many Marwaris courted imprisonment by participating in Bapu’s movements. Baijnath and Radhakrishan Bhavsinghka of Bihar were amongst them. Maganlal Bagari of the Central Provinces was awarded four years’ imprisonment in connection with the ‘Nagpur Conspiracy’.

In 1921 Moolchand Agarwal was sentenced to rigorous imprisonment for one year for writing inflammatory editorials in Vishwamitra. The government launched prosecution proceedings against Kanhaiya Lal Sethia for his revolutionary book Agnivina. Public functions began to be held to honour and support those who were sent to jail and suffered torture and hardships. Freedom fighters were taken in processions to the meeting venues in which the Marwaris participated in large numbers. Marwari women from all over the country also courted imprisonment. As revealed by Usha Gupta, Kusum Gupta played a significant role in the ‘Quit India Movement’ and was jailed.

Excerpt

The industrial entrepreneurship of the Marwaris rose to its peak after Independence. The Monopoly Inquiry Commission constituted in 1965 prepared a list of one hundred and forty-seven large industries which controlled the vital fields of production in India. It is believed that at one time nearly sixty per cent of industry in India was in the hands of the Marwaris. Their control over industry was more widespread geographically than that of their Gujarati counterparts.

Even today, the community bags many national and international awards annually for quality goods, innovative products, customer satisfaction, corporate social responsibility, and the like. By maximising exports, they have outdistanced other industrialists in earning foreign exchange. These trailblazing entrepreneurs have now turned their attention to the international market. They have not only explored markets of developed countries like the US, Japan, Australia, Britain and Germany but are playing an important role in the economic development of Kenya, Uganda, Afghanistan, Indonesia and Tanzania. Governments of various countries frequently invite them to assist and participate in enhancing their national economic development and growth.

Excerpt

If the Marwaris’ foresight and entrepreneurial leadership won them a name, their philanthropy endeared them to all. They were truly great and acted from passion. They founded numerous academic, scientific, industrial and economic research institutions. If charity was their passion, humanity was their religion.

They believed that money, which they earned from society, must go back to society. They even had a popular saying stating that when you donate from the right hand, the left hand should not be aware about it. According to their philosophy, ‘Nothing is ours; whatever God gave us has to be returned back to him.’ For them the quantum of donations was unimportant; it was the act itself that was important. They believed that the intention of giving should not be to gain fame; if it was then its value would be decreased to half and if one gained the fame then its value became one-fourth.

The Marwari Heritage

Author and Project Director: Dr D K Taknet

Publisher: International Institute of Management and Entrepreneurship (IIME), Jaipur

Price: R8,000 /-

The Marwari Heritage

SPECIAL 50%

DISCOUNT OFFER FOR

MARWAR READERS

Book your copy now

and pay `4,000 only,

against `8,000

Contact Bhautik Mehta

Tel: (022) 2481 1049

E-mail:

bhautik@spentamultimedia.com