A Revivalist Pursuit

For Pooja Singhal, the 41-year-old art enthusiast, and director of Ruh, a womenswear brand, her money is where her heart is. In conversation with MARWAR, she talks about her tryst with the Pichwai art form of Nathdwara and how she is determined to not let it disappear from contemporary vocabulary anytime soon.

Pooja Singhal is in the middle of finalising plans to take her revival project of Pichwai paintings to the India Art Fair 2016 and launch Ruh (her Delhi-based clothing brand for women) online when we find that precious window which allows us to have a chat with her. By the end of our interaction, all our initial observations converge on a single deduction: here is a woman to who striking the right balance between creativity and business comes naturally. Belonging to a business family from Udaipur [her grandfather P P Singhal set up Mewar Oil & General Mills Ltd., in Udaipur, in 1947, which was later renamed PI Industries Ltd.], Pooja Singhal as a child had been exposed to what business was all about.

As an adult, her involvement with the Delhi Crafts Council, a registered, voluntary, non-profit organisation that works for the development of traditional crafts and welfare of India’s artisans, sharpened her sensitivity towards natural fabrics, handloom and traditional appliqué, embroidery and block print techniques of India. Singhal launched Ruh in 2004 and has been working since with handloom including Maheshwari cotton, Kerala cotton, khadi and chanderi, to create womenswear that is Indian in make, but Indo-western in style.

It was during her formative years that a proclivity towards art took root. Her mother, Madhu Singhal, had an eye for paintings, and would often promote and buy the works of Pichwai artists who would come from Nathdwara to visit her. Nathdwara, a sleepy town a few kilometres away from Udaipur, was the birthplace of Pichwai, one of the most intricate works of art executed on cloth and paper. “I grew up with Pichwais; my mother would often take me on shopping expeditions to Nathdwara to buy the paintings,” she says.

Five years ago, when she realised the Pichwai art form was not getting the attention that it deserved in the mainstream of India’s ancient arts, Singhal began working with artists in Nathdwara and areas near Udaipur to reproduce old works and come up with modern interpretations. “Through Ruh, I had addressed a gap in the market for a ready-to-wear apparel brand with designer details, refreshing looks and affordable price tags. My business acumen, my passion for the arts and sense of design, along with my MBA degree from the University of Pittsburgh came into play and helped me create the brand, price the collections, make them sell and build a clientele. I was required to do more or less the same things when it came to my Pichwai revival project,” she says, adding, “An art dies if it doesn’t sell. The more the appreciation, the more it sells; this makes sure that the art survives the test of time.”

The Pichwai palette

Rajasthan has long been celebrated for its art and culture; many of the finest art forms have flowered in its villages  where they have served as modes of creative expression and communication. And the temple town of Nathdwara had its very own unbroken artistic tradition—of dark and richly hued paintings—that came to be designated as ‘Pichwai’. Painted, printed with hand blocks, woven or embroidered, Pichwais largely narrate the many episodes from the life of Lord Krishna, in his form as Shrinathji. Some depict his chowbeeswaroop or 24 divine forms, while others depict him surrounded by his beloved gopis (cowherd girls), celebrating his birthday, becoming a bridegroom, or as the centre of Janmashtami festivities. Pichwais were initially developed as a backdrop to the idol of Shrinathji in the sanctum sanctorum of the Nathdwara temple of Udaipur. Singhal shares, “In the 17th century, only five families of the Vallabhaichari sect [that worshipped Shrinathji] would create the carefully composed renderings on cloth that is hung behind the idol.” Traditionally, the cloth used for Pichwai was starched and hand spun, on which colours derived from ground, semi-precious stones were used. “Today, Pichwais are created on finely mercerised cotton or handmade paper called basli.”

where they have served as modes of creative expression and communication. And the temple town of Nathdwara had its very own unbroken artistic tradition—of dark and richly hued paintings—that came to be designated as ‘Pichwai’. Painted, printed with hand blocks, woven or embroidered, Pichwais largely narrate the many episodes from the life of Lord Krishna, in his form as Shrinathji. Some depict his chowbeeswaroop or 24 divine forms, while others depict him surrounded by his beloved gopis (cowherd girls), celebrating his birthday, becoming a bridegroom, or as the centre of Janmashtami festivities. Pichwais were initially developed as a backdrop to the idol of Shrinathji in the sanctum sanctorum of the Nathdwara temple of Udaipur. Singhal shares, “In the 17th century, only five families of the Vallabhaichari sect [that worshipped Shrinathji] would create the carefully composed renderings on cloth that is hung behind the idol.” Traditionally, the cloth used for Pichwai was starched and hand spun, on which colours derived from ground, semi-precious stones were used. “Today, Pichwais are created on finely mercerised cotton or handmade paper called basli.”

Traditional art forms tend to lose their deeper significance when confronted with commercialisation. There is also a shift from the traditional motifs and themes, which tend to erode the artworks’ pristine quality and value. The same holds true for Pichwais, Singhal says, explaining the commercialisation of Pichwai in the past few years and how, as a consequence, the artist-turned-craftsman didn’t pay much attention to quality, thereby impairing the aesthetic of Pichwai paintings. “Udaipur, once the best place to source original Pichwais, was now flooded with badly made versions created by using stencils and spray guns. Colours used originally, created by grinding of stones, had been swapped with pigment paints, and several of the original designs had been forgotten,” laments Singhal. The number of artists had diminished since their children weren’t interested in taking the art forward. “Insiders will tell you that while earlier there were around 2,000 Pichwai artists, the number dropped to around 400.”

Making artwork accessible

Singhal’s voice bubbles with excitement as she launches into the nitty-gritty of the restoration process and the responsibilities that come along with it, “My idea is to make the style accessible to a larger clientele, while ensuring traditional styles remain alive.” Coming from someone else, this sort of mission might appear grandiose, but Singhal’s eagerness is difficult to ignore. So what exactly does she do to drive the message home? “It took me two years to rope in traditional artists who live in Udaipur and commission them to execute the works, staying true to the original styles and techniques (such as reviving the use of stone colours, as opposed to pigments). After a great deal of research and poring over catalogues and private collections of art collectors, we have reproduced compositions that are original and beautiful,” she says.

The intervention on Singhal’s part has been a merging of different styles of Pichwai paintings, which include the Kota style, featuring a minimalist approach and brisk brush strokes; and the Deccan style, featuring gold and silver foil in the stone colours. By having pieces made in monochromatic colours, she attempted to make the art suit modern tastes and decor sensibilities. “I have also resized the Pichwais to make it easier for people with smaller apartments to display them.” Singhal today works with 25 to 40 artists, with groups of four-five artists working on each painting. “Sometimes, there is a master artist, and sometimes there is more than one artist working on a relatively smaller painting.”

Brushing perceptions aside

According to Singhal, “When you look at a Pichwai painting, it is unusual since there are so many things happening in just one painting… yet it looks beautiful and well-balanced. It’s an art form that has gained international recognition, even attracting the attention of auction houses such as Christie’s, New York and Sotheby’s. Recently, the Art Institute of Chicago also held a Pichwai exhibition.”

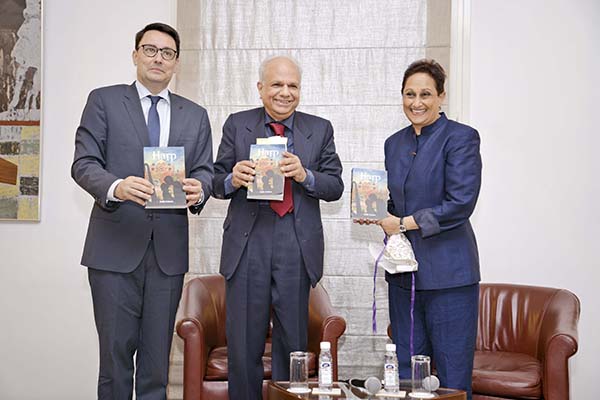

The desire to change the perception of people and showcase Pichwai in a contemporary way is what pushed Singhal to organise an exhibition of over 80 Pichwai paintings in a beautiful 1950s bungalow at Jor Bagh, New Delhi, last year. The private preview was unveiled by Shriji Arvind Singh Mewar of Udaipur on September 22, 2015. On the opening night of the exhibition, art critic Gayatri Sinha did a curated walk, which was followed by a talk by Desmond Lazaro, a British artist who’s studied the ancient tradition of miniature painting, especially that of Pichwai. Singhal too did a curated walk for some ambassadors and expats. The exhibition, which was on till October 9, saw attendance from students of National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT).

Challenges on the way

When asked how tough it is to restore an ancient art form and make it appealing for the modern generation, Singhal says, “A difficulty I often face is explaining the importance of ‘quality’ to my artists. Often, the work lacks finesse; or there is no consistency and the colouring is uneven. Grinding the colour stones requires work, and if artists don’t put in the right amount of time, the colours don’t shine through. Sometimes, artists paint the eyes of Shrinathji crooked, or if they make a mistake with the proportion of the border, they try to cover it up by increasing its width, thereby changing the whole look.” And what is the most demanding aspect of her job? It is making sure that the artwork commissioned comes out the way she planned. “The biggest worry is whether the piece that will emerge months later will be at par with my expectations.”

Painting a better future

Backed by her family’s agrochemical business, Singhal is studying the chemical compositions of colours and discovering effective substitutes. She says, “Traditionally, the colour yellow used in Pichwais came from the urine of cows that had been fed mangoes—such a practice cannot be followed anymore.” And what will she be working towards in the future? “I have showcased Pichwais at the India Art Fair this January and am currently in talks with Kochi-Muziris Biennale, India’s first biennial of international contemporary art, for a Pichwai show as one of their collateral events.”