A Generational Saga

Sujit Saraf’s novel The Peacock Throne captured the political and religious contradictions of modern India. It was shortlisted for the Encore Award and won the author international acclaim. Another book, titled The Confession of Sultana Daku, was a fictional reconstruction of the fearsome bandit who terrorised the United Provinces of British India in the 1920s. It is now being made into a motion picture.

Sujit has pursued his literary aspirations with aplomb, despite having a day job as a software engineer in the US and writing only on the weekends. He says, “I do not even think of this as a transition. Words are as precise as numbers, and a well-formed sentence is as clinical as a mathematical equation. I have found literature to be astonishingly like science and technology—they demand logic, imagination and precision.”

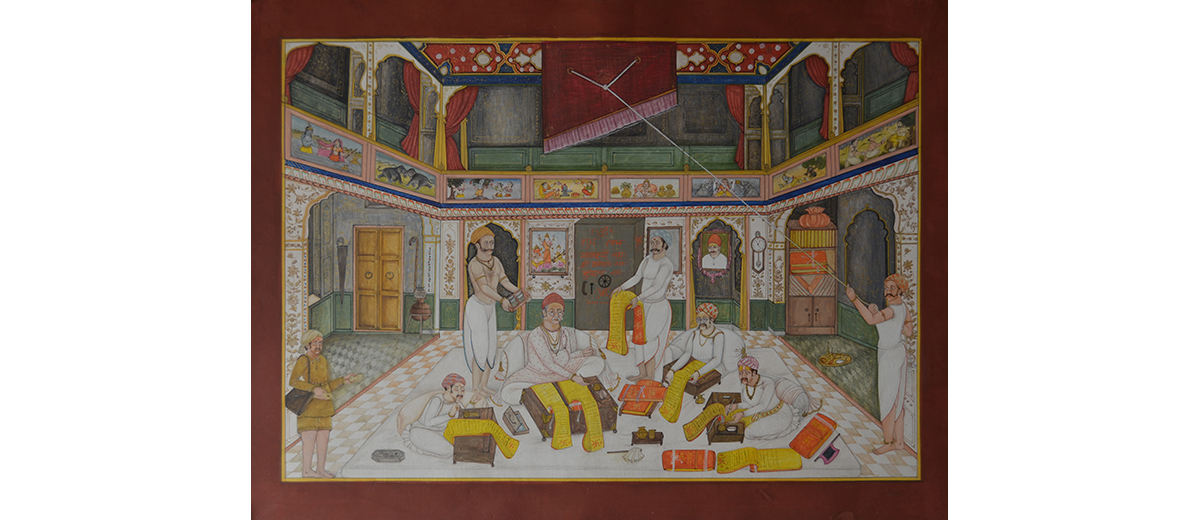

We bring you a tête-à-tête with the author, who has just penned Harilal & Sons, a generational saga that captures India’s Marwari community in an evocative and powerful narrative.

What motivated you to write Harilal & Sons?

My grandfather died nine years before I was born.

In those nine years, everything they said about him had become wrapped in the pieties that are usual about dead forebears. In keeping with the times, my father was uncommunicative when it came to information about his father. No one, in fact, was able to recall the name of my grandfather’s first wife. All I had to remind me of him was a photograph hanging in my father’s shop, showing a stern man seated in a chair. The idea of a sweeping story about that man, emblematic of the world of Marwaris, has been with me for a while.

How difficult/easy was it to write about one’s own community?

It was simple, in the sense that I grew up in a conservative Marwari household in a small town in Bihar. My mother recited the Sunderakand every evening; she had never seen an egg at close quarters; and she organised a Satyanarayan Puja once a year. Although I was sent to a boarding school in the hills and then found my way to Delhi and the West, the village was never taken out of the boy.

Yet it was difficult to write this novel, in some ways. This is a personal tale. It is impossible for me not to get sentimental about it, to regard the man and his story objectively. Indeed, I sneaked myself into the story; one of the little brown boys who appears in the last chapter is me.

Also, how does one write a story from the inside? How does one appreciate that however much a tale may appeal to him, the world perhaps has little interest in it? To me, my grandfather’s journey to East Bengal is momentous—it determined where I would be born and who I would grow up to be. To the reader, it is just a plot twist.

There are countless Marwari set-ups that also span generations. Were you inspired by any of them while penning this novel?

Yes, of course—my own family business and those of my uncles, relatives and extended family. When growing up, everyone I knew was running one of the businesses mentioned in Harilal & Sons, sitting behind cash boxes, selling soap, textiles, tobacco, grain, jute… All my descriptions are from personal experience, suitably modified when situated in the previous century.

Your book captures the roots of the Marwari community, their work ethic and their rise against the backdrop of a country in evolution. What kind of research went into it?

I spent some time in obscure Kolkata libraries, which are full of vanity projects—rich Marwari seths often wrote, or paid someone to write, their life histories. These were hagiographies celebrating this or that business empire read by no one but family members of the seth, but they contain a mine of information that is of no value to anyone but prying writers like me!

The rest of my research was general—an investigation of the world around Marwaris rather than Marwaris themselves. Finally, of course, much of the book derives from personal experience—I am a Marwari man writing about Marwaris.

There are certain stereotypes associated with the community. Do you believe in telling things as they are or do you look to challenge stereotypes through your characters?

These stereotypes are simplifications of complex truths, but they do contain a grain of truth. I chose neither to challenge them nor to emphasise them. They exist in all their complexity in the novel. I do not want to impose my values, or the values of a Western liberal world, on a man who lived a hundred years ago. He was a man of his times, and I am content to let him be that.

Historical Indian fiction in English has relied on the accounts written by Englishmen of their time in India, leading to a limited perspective. Even today, there are few writers who dabble in it. Why are Indian writers particularly averse to this genre?

Most Indian writers in English went to ‘English medium’ schools in cities and now live in the West. They write primarily for Western readers (I am describing myself!). There are no rewards for the lonely writer who chooses to situate himself or herself in the Indian milieu, or to write in Indian languages. We try. Or, we try against our better instincts! This novel is perhaps my attempt in that direction. I can afford to do so because I do not rely on writing for my livelihood.

Tell us a little about yourself.

My grandfather migrated from Shekhawati to a town named Bogra in East Bengal (as in the novel), where my father was born. In 1947, he moved his whole family westward to Jalpaiguri and Calcutta (now Kolkata) in the newly created state of West Bengal, and then to a small town named Katihar in Bihar (I renamed this town in the novel). I was born there, and sent to a boarding school run by Irish missionaries in the Darjeeling hills because, said my father, “They force you to speak English there”. Sure enough, I was singing Beatles songs when I came home for vacation. They drummed English into me but were somehow unable to squeeze out Hindi. I then went to St Columbas School in Delhi, followed by IIT.

Like the rest of my IIT class, I went to the US for postgraduate study, got a Ph.D. from Berkeley, worked for NASA, returned to India to become a professor at IIT, then retreated to Silicon Valley again, where I spent a decade working as a space scientist. I now work for a software company and live in San Jose, California, with my wife, daughter and son. In my spare time, I run a large Indian theatre company, NAATAK, for which I regularly write and direct plays.

What’s next on the agenda?

A novel set in America—my first to be set outside India. In July, I will stage a grand musical adaptation of Saadat Hasan Manto’s Toba Tek Singh.