Preserving a Heritage

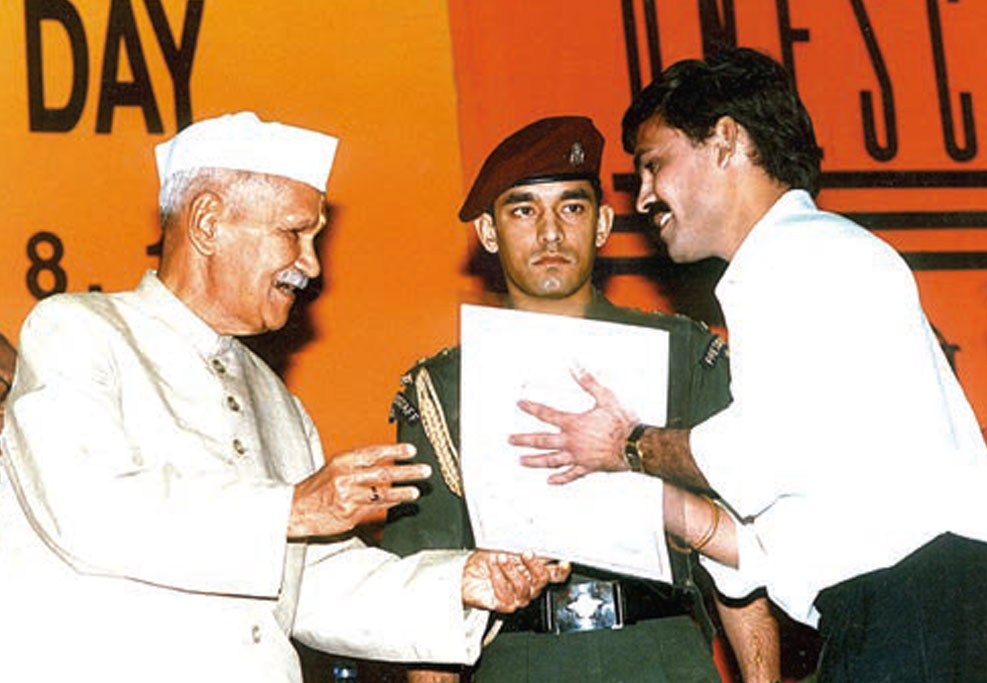

(Lakhi Chand Jain receiving national award from the then Hon’ble President of India, Dr Shankar Dayal Sharma, 1996 ; Top right: Lakhi Chand Jain creating a Mandana on the floor)

In a world forever changing due to rapid urbanisation, there seems to be little or no space for traditional art forms to survive. Luckily, around 25 years ago, artist Lakhi Chand Jain took it upon himself to breathe new life into the dying Rajasthani art of Mandana painting by reinventing it with his unique brand of Mandanagraphy.

It’s hard to miss the stark white intricate patterns of Mandana folk paintings against the earthy red floors and walls of village homes across Rajasthan. Once drawn by the skilled hands of the women of the house in a bid to protect the home and mark the start of festivals, these paintings are deeply rooted in the rural landscape of the past. Seeking to revive this vanishing art form, Mumbai-based artist Lakhi Chand Jain began to use an assortment of textures, canvasses and new media for his Mandana paintings, a little over two decades ago. Thanks to his efforts, the art form has made its way from the floors and walls of Rajasthan into the living rooms of city dwellers in India and, quite possibly, other parts of the world.

Lakhi Chand has created over 300 Mandana paintings in various sizes, on both floor and canvas since he started working with the art form. Mandanagraphy, his adaption of the traditional art, is a portmanteau of the words ‘Mandana’ and ‘graphy’. Comparing it to photography, the art of capturing objects or scenes through a camera lens and presenting the image on different surfaces, he says that Mandanagraphy captures the object or subject through the lens of his imagination.

Top (clockwise from left) ‘Saatya Ka Jod’, Swastika yantra by Lakhi Chand Jain©; ‘Binayak Ji Ka Mandana’, Lord Ganesha on canvas; Lakhi Chand Jain has been honored with the National Youth Award, 1990-91 (Govenrment of India); Lakhi Chand Jain has been honored with the Shiv Chhatrapati State Youth Award, 1988-89 (Government of Maharashtra), A floor Mandana depicting the five elements of ‘panchmahabhuta’

Rooted in village folk life

Lakhi Chand comes from a family that once dwelled in Rajasthan. Over 125 years ago, a great famine in the state forced thousands of Rajasthani-Marwari families to abandon their homes, leaving many villages empty and deserted. His ancestors too left and travelled to Maharashtra in search of a livelihood. “They settled in Pahur, a tiny village on the bank of the Waghur River in the Jalgaon district of Maharashtra. I was born in this village and my early childhood was spent in an earthen house,” says Lakhi Chand, who learnt the art of Mandana from his mother and grandmother.

The word Mandana is derived from the Sanskrit word ‘Mandan’, meaning ‘to express’ or ‘to explore’. For practitioners, Mandana is not just an art form; it is deeply seated in village folk life. It helps the flow of positive energy in homes, keeping inner emotional feelings and artistic beliefs alive, maintains Lakhi Chand, adding that folk tales transmitted orally from one generation to the next have helped keep this narrative alive. “These folk stories give us something to learn, without promoting any kind of blind faith. They inspire us to perform good deeds and make us culturally literate,” he says. Historically, Mandanas also found an important place in the compositions of Rajasthan’s poets and folk musicians, which, the artist says is a testimony of how deep the roots of Mandana run in village folk life.

The artist as researcher

Lakhi Chand’s passion, Mandana, has also found an outlet in his extensive research on the history of the art form. Consequently, he is a treasure trove of knowledge now and is often invited to impart his knowledge and skills at workshops for art enthusiasts in India. “Mandanas are characteristically different from folk art like Kohbar (Bihar), Jhoti or Chita (Odisha), Pithoora (Madhya Pradesh), Warli (Maharashtra) and other styles that are an intrinsic part of mudhouse architecture in India,” he explains. Traditionally, the process of creating a Mandana painting begins by first coating the floor or wall with cow dung, before creating the basic canvas using earthen terracotta. Then, with the help of the ring finger, the Mandana is painted using white khadiya, or a paste of lime stone. They are also created using unique brushes fashioned out of twigs of date palm trees, fastened with a cotton swab on one end.

A visual language

“Mandana paintings don’t have a storyline,” explains Lakhi Chand. Wall Mandanas commonly consists of spontaneous freehand drawings of animals, birds, flowers and plants, while the floor paintings—a play of very simple, uneven bold lines—depicted geometric and inanimate forms that attempt to explore meditation, spirituality and sexuality. While he has created a unique series of Mandana paintings that feature peacocks, deer, roosters and hens on both craft paper and canvas, he has also explored many new forms based on household objects and sports that were a part of his childhood. He is currently engaged in a unique project called ‘Art of Relevance’, which is his attempt to use Mandanas to make the public think about inner peace, joy and the importance of folk art in day-to-day life.

Lakhi Chand’s adaptations might have found a drastically new canvas, as his paintings adorn everyday utilities like umbrellas too. Yet, his Mandanas don’t deviate from the traditional aspects of the art, even though his work is tinged with innovations. Years of experimentation led him to replicate the texture of mud walls by creating his own pulp of watersoaked newspapers mixed with natural gum, yellow ochre soil, cow dung and other natural elements.

The artist’s life

Over the years, Lakhi Chand has been lauded for his efforts in preserving this near-extinct art form. He is the recipient of three national awards, including the National Youth Award (1990-91), India’s highest youth honour. More recently, Lakhi Chand Jain has been conferred with the ‘Marudhara Samman, 2016-17’ for his creative efforts and outstanding contributions to the revival of Mandana art.

As much as awards serve as a momentous reminder of a lifetime of hard work and dedication, life as an artist is never easy. This is more so the case when physical challenges become an obstacle in one’s quest to revive an art form. “In the past, it was possible for me to raise funds. But for the last eight years, especially after I started to suffer from a permanent orthopaedic disability, the search for funds has been my biggest challenge,” says Lakhi Chand. “Besides, due to the lack of space, every Mandana has to be done keeping in mind many of the limitations. It’s also a challenge for me to keep the purity and folk ambience of the art alive while shaping this art in modern mediums.”

He believes that it will take more than just government aid to promote the art of Mandana, when he says that every individual who is linked to the soil of Rajasthan must do their bit. He even hopes to create an interactive Mandana museum, perhaps, in Jaipur, Jodhpur, Udaipur or Sawai Madhopur—not only to conserve the art form, but also to promote tourism. He has also just wrapped up the first draft of a book on Mandana that he hopes will find form as a coffee table book in Hindi and English.

While Lakhi Chand is optimistic about the sustainability of Mandana, he adds that like most ancient arts, it is impossible to predict the nature of this art in the future. “At present, due to modernisation, this art form is facing the same circumstances as a dried-up river. After crossing this phase, there will be a new change; the canvas will be different. All folk art decides when it needs a makeover. Sometimes, even rivers have to change their course,” he says. Fortunately, we have an artist in our midst who believes in keeping up with a world that’s swiftly changing before our very eyes.