Kolkata Reloaded

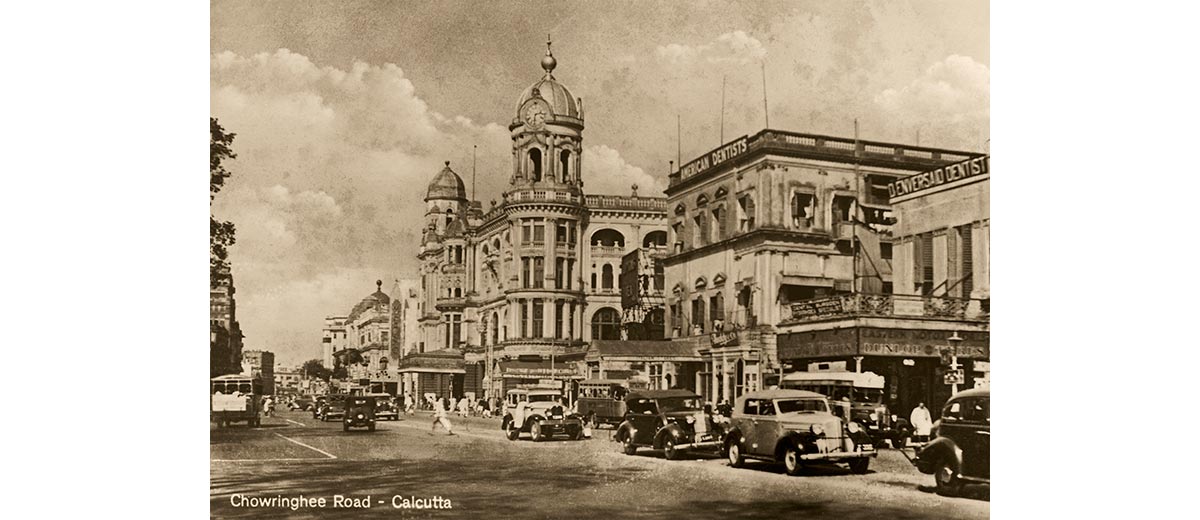

Kolkata, unlike Mumbai, has never really been known as a city of high-rises. For a long time, before the South City condos came up in 2008, the tallest building in the city remained the Chatterjee International Centre, a 24-storeyed building that is just shy of 300 ft. Located at Chowringhee, the historic central business district, the building is memorable: the beautiful facade displays a primarily green and blue mosaic that depicts a giant cross on three panels, each of which bears one of the three words that make up the building’s name.

The tallest building in eastern India (at the time of its construction in 1976) also became symbolic of something less noble: of dwarfed and sluggish growth, complacence and a stunted economy. For, while a 24-storeyed building was considered an achievement in Bengal, Mumbai’s World Trade Centre at Cuffe Parade, built around the same time, was more than 10 storeys and 200 ft higher. While Delhi and Mumbai surged ahead in terms of development, India’s cultural capital seemed stuck in time, basking in its discomfiting resistance to change, dilapidated mansions and growing squalor.

The tallest building in eastern India (at the time of its construction in 1976) also became symbolic of something less noble: of dwarfed and sluggish growth, complacence and a stunted economy. For, while a 24-storeyed building was considered an achievement in Bengal, Mumbai’s World Trade Centre at Cuffe Parade, built around the same time, was more than 10 storeys and 200 ft higher. While Delhi and Mumbai surged ahead in terms of development, India’s cultural capital seemed stuck in time, basking in its discomfiting resistance to change, dilapidated mansions and growing squalor.

Mall boom

It was as late as 2002 when Bhowanipore in South Kolkata saw Rahul Saraf’s multicoloured Forum Mall pop up, transforming the erstwhile residential locality into a high-street shopping destination with its handful of international brands, an INOX (the first multiplex in the city) and a food court. Its predecessors—which couldn’t flaunt popular food outlets or international brands, and generally lacked all the sophistication that the Forum Projects offering smacked of—were the sort of places where no self-respecting teenager would be caught dead in. In those days, to have a true ‘mall’ experience, Kolkatans had to venture to Delhi and Mumbai. Since then, however, Kolkata has emerged as a retail hotspot, with many more malls (including Forum 2 and, more recently, RP-Sanjiv Goenka Group’s luxury mall Quest) mushrooming in the southern areas—the newer, more modern part—of the city.

It was as late as 2002 when Bhowanipore in South Kolkata saw Rahul Saraf’s multicoloured Forum Mall pop up, transforming the erstwhile residential locality into a high-street shopping destination with its handful of international brands, an INOX (the first multiplex in the city) and a food court. Its predecessors—which couldn’t flaunt popular food outlets or international brands, and generally lacked all the sophistication that the Forum Projects offering smacked of—were the sort of places where no self-respecting teenager would be caught dead in. In those days, to have a true ‘mall’ experience, Kolkatans had to venture to Delhi and Mumbai. Since then, however, Kolkata has emerged as a retail hotspot, with many more malls (including Forum 2 and, more recently, RP-Sanjiv Goenka Group’s luxury mall Quest) mushrooming in the southern areas—the newer, more modern part—of the city.

Today, the middle-class-dominated Jodhpur Park in the south is home to the swanky South City Mall and condominium, promoted by South City Projects (and run by Marwari heavyweights including the Mohtas of Merlin Group of Companies, the Agarwals and Goenkas of Emami Group, the Khetawats of Rameswara Group, the Surekas of Sureka Group, the Todis of Shrachi Group and the Bachhawats of J B Group). What was for decades touted as a ‘dead’ city had suddenly woken up and Kolkata’s resurgence was being etched in concrete.

A shift in scene

However, it wasn’t long before the eastern part of the city too headed for a makeover. When Ambuja’s Udita, on the Eastern Metropolitan Bypass (commonly referred to as ‘E M Bypass’ or ‘the Bypass’), came up in 2001, it was a one-of-its-kind venture for the upper middle class of Kolkata, equipped as it was with a tennis court, a swimming pool, a gym, a banqueting space, children’s play areas, landscaped gardens, an amphitheatre and a jogging track. Harshavardhan Neotia, Chairman, Neotia Ambuja Group, notes that Udita was not about “uber luxury” which is precisely why it was built at the Bypass, which was perceived more as a middle-class area at

However, it wasn’t long before the eastern part of the city too headed for a makeover. When Ambuja’s Udita, on the Eastern Metropolitan Bypass (commonly referred to as ‘E M Bypass’ or ‘the Bypass’), came up in 2001, it was a one-of-its-kind venture for the upper middle class of Kolkata, equipped as it was with a tennis court, a swimming pool, a gym, a banqueting space, children’s play areas, landscaped gardens, an amphitheatre and a jogging track. Harshavardhan Neotia, Chairman, Neotia Ambuja Group, notes that Udita was not about “uber luxury” which is precisely why it was built at the Bypass, which was perceived more as a middle-class area at

the time.

Today, in sharp contrast, the Bypass is a hub of activity, leading to an increase in land prices and traffic—and hipsters and inner-city elite alike—in the area, which is likely to continue to see an influx of luxury hotels, educational institutions, convention centres, speciality hospitals, malls and multiplexes. Neotia notes that the Bypass is now going to have a metro route on it as well and predicts that it will be a major thoroughfare in the near future, even calling it ‘the Chowringhee of tomorrow’. “The prices of properties have risen considerably,” he says, adding, “When we started in 1995, the rate per sq ft for our apartments was about r700. At that same location, it is `7,000, today! Of course, in certain parts of the Bypass, which are closer to the city, the prices go up to r15,000-16,000 per sq ft, also,” he concludes.

Merlin Group’s managing director, Sushil Mohta is building Acropolis, a 3,00,000-sq-ft mall that is slated to open soon on the Rashbehari-EM Bypass connector. The current president of the Bengal chapter of the Confederation of Real Estate Developers Association of India (CREDAI) says, “In recent years, the EM Bypass region in Kolkata has been witnessing several major projects in health-related sectors, apart from residential and commercial properties. I believe, these will signal a paradigm shift in the way ‘downtown’ has been perceived in Kolkata.The proximity to important medical institutions—Fortis, Desun, Ruby, Peerless and R N Tagore Heart Institute—five-star hotels and premium serviced apartments also signposts the explosion of medical tourism in this region. Recent trends show that companies are snapping up Grade A office spaces in these emerging business districts with gusto.”

Merlin Group’s managing director, Sushil Mohta is building Acropolis, a 3,00,000-sq-ft mall that is slated to open soon on the Rashbehari-EM Bypass connector. The current president of the Bengal chapter of the Confederation of Real Estate Developers Association of India (CREDAI) says, “In recent years, the EM Bypass region in Kolkata has been witnessing several major projects in health-related sectors, apart from residential and commercial properties. I believe, these will signal a paradigm shift in the way ‘downtown’ has been perceived in Kolkata.The proximity to important medical institutions—Fortis, Desun, Ruby, Peerless and R N Tagore Heart Institute—five-star hotels and premium serviced apartments also signposts the explosion of medical tourism in this region. Recent trends show that companies are snapping up Grade A office spaces in these emerging business districts with gusto.”

As a premium mixed-use development project, Acropolis is an approximately R400 crore public-private partnership (PPP) between Kolkata Metropolitan Development Authority (KMDA) and the Merlin Group. For Acropolis, the EM Bypass region—Kolkata’s emergent central business district—is a strategic location that will tap into an expansive primary catchment area comprising a huge chunk of South Kolkata.

Things are certainly looking up for the city with a colonial hangover, with the exception of the ancient north which has always remained the same: a maze of narrow lanes and crumbling mansions … It was as if it didn’t quite require the “anglicisation and stock gestures of ‘being modern’ that the Southerners embraced and strutted”, as journalist Indrajit Hazra notes in his book Grand Delusions. Many proud Northerners contend that it is politics that is holding them back. Both Didi (as Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee is better known) and ex-mayor Subrata Mukherjee are South Kolkatans after all. But the truth bends towards labour disputes and bad infrastructure—and the inane cost implications therein—which don’t make monetary sense for any builder, no matter how big.

A tale of two townships

The adjacent townships of Bidhannagar (also known as Salt Lake City because it was built on a reclaimed saltwater lake) and the newer New Town, in the north-eastern fringes, are no longer regarded as remote or inaccessible as they once were. The former hosts IT hubs (Sector III and V) and notably employs more than a lakh of people. The major software companies located here include TCS, Accenture, ArcelorMittal, Wipro, IBM and Larsen & Toubro. Keeping in mind the deluge of recent developments, it is hard to grasp that the first mall and recreational centre—Neotia’s City Centre 1—for the residents of Salt Lake City was completed only in 2004. “Bidhannagar is a planned satellite town which was originally developed between 1958 and 1965 to accommodate the burgeoning population of Kolkata, with Sector V being predominantly targeted as an electronics industry hub. However, in the last decade, with a boom in the IT market, the government has proactively positioned Sector V as an IT hub. This move saw Sector V blossom into Kolkata’s own Silicon Valley,” illuminates Pradeep Sureka, the managing director of Sureka Group.

New Town, on the other hand, which started growing in the late 1990s, was envisioned to be at least three times bigger than the neighbouring Salt Lake City. The nine-storeyed Swissôtel Kolkata Neotia Vista—a joint project of Ambuja Realty and the Swiss hospitality chain—shares space with City Centre 2. Kolkata’s first hotel in a mall, it was built as a business hotel, keeping in mind its close proximity to the airport (a swanky steel and glass structure since last January) and Sector V. Already declared a Solar City, New Town is vying for the Smart Green City status too. Initiatives which qualify it for the title include the 10.5-km, Wi-Fi-enabled Rajarhat Main Arterial Road (that connects the airport to Sector V), energy-efficient devices (like LED lights) and a vehicle-tracking system for solid waste management, all of which make the area more business-and-environment-friendly.

Changing for the better

If market sentiments are anything to go by, mixed-use properties in the North 24 Parganas district (which houses both Salt Lake City and New Town) could well emerge as the new business destinations of the city. With their infrastructure and world-class amenities, these New Age integrated developments are nudging companies to move out from the cramped office areas of Central and North Kolkata.

Many Kolkatans feel that the changing face of real estate is not a boon. Rather, it is a move towards consumerism, as is best exemplified by the advent of malls. While it’s true that malls don’t equate with modernity, what cannot be refuted is the spawning of the ‘mall generation’, a new generation of westernised youngsters who spend a large chunk of their free time in air-conditioned malls, and the impact they have had not only on the culture of our city but also on the psyche of its residents—some for the better and some for the worse. But we are not talking about what defines ‘development’ here. That is a different story.

These recent developments have made Kolkata immeasurably more attractive to many locals, diasporic Kolkatans and tourists. They have also ensured that a hundred years after it stopped being the capital of India, Kolkata has also finally stopped being India’s capital of stagnation.